Nanjala Nyabola is a writer, political analyst, and activist based in Nairobi, Kenya. She writes extensively about African society and politics, technology, international law, and feminism for academic and non-academic publications. She has written Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics and her most recent book, Travelling While Black: Essays Inspired by a Life on the Move, has been positively received by literary reviewers worldwide.

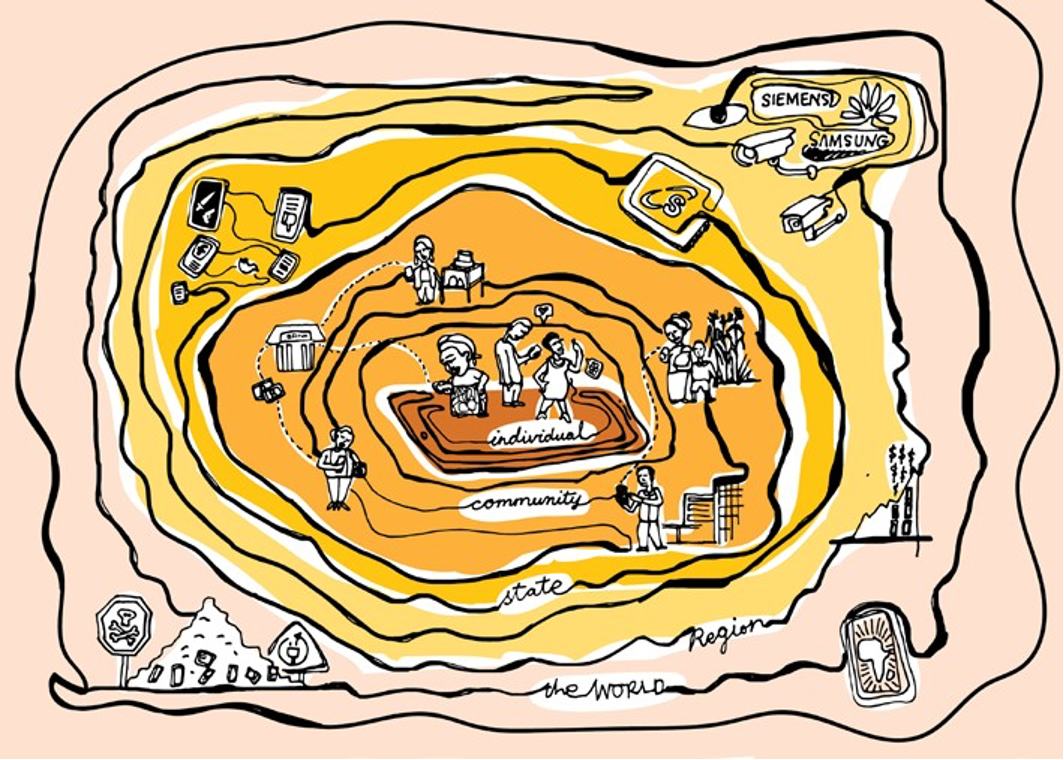

Nanjala Nyabola is editor and contributor of Vertical Atlas. In her essay, The Phone Changed Everything, Nanjala Nyabola sheds a light on the political economy of the mobile phone in the context of Kenya. Borrowing the tools of geography Nyabola illustrates how the object intersects with power at different levels

of society.

The phone changed everything

By Nanjala Nyabola

One of my favourite memes from the last few years shows two desks side by side: one desk, from as late as the 1990s, is littered with a calculator, telephone, computer, camera, fax machine, and other devices; on the other desk, a mobile phone. Both desks display the exact same functionality. But the mobile phone has the capacity to do the same things while also fitting into your pocket. More than just shrinking the effective mechanisms in the various objects on the first desk, the evolving technology of the mobile phone introduces new artefacts of decision-making by the people who manufacture, service, and regulate these devices. In a new era defined by connection and disconnection, the politics of the mobile phone brings many debates –surveillance, state power, the ethics of data collection, privacy, and more – into sharp relief.

You cannot understand how technology will affect a society unless you understand the society in question.

Perhaps more than any other object, the mobile phone embodies the promises and the contradictions of the twenty first century. While contemporary objects are increasingly standardised in their production and global in their distribution, all objects collide differently with different societies, and every innovation looks different at various levels. This is the main argument of my book, Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet Era Is Transforming Politics in Kenya: you cannot understand how technology will affect a society unless you understand the society in question. Our societies are products of specific histories and relationships, and a new object will adapt to whatever cleavages it finds in those societies. Therefore, you cannot fully illuminate the politics of the mobile phone without understanding the pre-existing cracks and cleavages in the societies or social units that use that device. An object is more than its form—it also constitutes design and utility choices; moreover, it represents the interests and capacities of the person who uses it.

How can we map these dynamics effectively, thus capturing the social, economic and power dynamics that an object encounters, adapts to, aggravates and attenuates? Words are good, but images can help. What follows is a rudimentary breakdown of the political economy of the mobile phone, borrowing the tools of geography to illustrate how the object intersects with power at different levels of society.

The individual

The SI unit of any society is the individual. It is the individual who buys the phone and turns it into a useful object that responds to their specific demands. Social behaviour is thus an aggregate of individual preferences and choices. But who do we acknowledge in the pivotal role of the individual when we talk about any piece of technology, especially the mobile phone? Our conversations about technology are shaped by power dynamics that obscure the specific experiences of individuals from various backgrounds. The unspoken politics of access, needs, and power lie beneath the conditions we accept as given.

We often assume, for example, that the mobile phone user is urban and educated, sometimes a teenager, almost always a man. How does our understanding change when the individual at the centre of our power analysis of the mobile phone is a woman, not a man? Consider the question of privacy. Apps that collect and monetise the private health information of individuals have routinely been challenged in both policy discourse and the law. Google has been sued in multiple judicial systems for collecting incidental health data from people’s mobile phones; in Europe, they are now forced to seek the consent of the individual before using their data for other reasons.

Until recently, however, certain particularly invasive apps have escaped serious scrutiny because they provide services tailored for women. Period tracking apps, for example, are able not only to collect vast amounts of individual health data but also to make incredibly accurate extrapolations and predictions regarding one’s personal life. These apps have been selling user information to bigger online players with little oversight, despite the obvious potential for harmful consequences for the user in the long run, for instance, in their access to health insurance. By 2020, none of the major period tracking apps can confirm that the data they collect is only used to track periods – seemingly reserving the right to use them for something else…

Kenyan researcher Brenda Sanya pushes us to think critically about how underlying political dynamics can affect the use of mobile phones, as well as how the use of mobile phones can unsettle existing social concepts. For example, how does our understanding of “literacy” change when we see nominally illiterate rural women learning to use text-based USSD mobile money systems?*

The community

Every individual, unless they are a hermit, is part of a community, connected to the people who enter, exit, and affect their lives. At the community level, therefore, objects intersect with power through connections and disconnections, social hierarchies, and ideas of belonging – especially in the case of objects like the mobile phone, whose entire purpose is to connect people to one another more intensely.

In Kenya, the mobile phone’s impact on rural-urban connections has been especially acute. In sociological terms, Kenya would be described as a “dual system,” in which people migrate to urban areas and leave families in the countryside. This sets up a domestic system of dependence and remittances, for example, where families in rural areas are dependent on regular cash infusions from urban-dwelling wage employees to meet their subsistence needs. The origins of Kenya’s dual system can be traced to the British colonial period (1895 – 1963), when the levying of oppressive poll and hut taxes compelled black men to move to urban areas in search of wage employment, while the institution of racist policies forbid those men from living with their partners and families in the apartheid towns.

An object is more than its form–it also constitutes design and utility choices; moreover, it represents the interests and capacities of the person who uses it.

Traditionally, families relied on twice-yearly visits or informal systems to send money home. Some used money orders or postal orders to make the transfers, incurring prohibitively high fees from predatory finance companies like Western Union and Money Pay. But the mobile phone changed everything, particularly in 2006 with the launch of Safaricom’s M-Pesa, the first mobile money system in the world. This new USSD system allowed individuals to send money instantly all over the country, and gave recipients the options either to keep the money in deposit as pre-paid airtime credits – freeing up other money in the household budget – or to withdraw the money as cash from a Safaricom dealer.

Today, Kenya’s market for mobile money (dominated by three large mobile companies) is per capita the largest in the world. In 2017, the volume of mobile money transactions in Kenya was equivalent to one-third of the national GDP. The system was enormously popular and successful in its adoption by communities, but it also shifted community dynamics in the country considerably. Large banks that once charged exorbitant fees for even the simplest transactions have been forced to completely overhaul their business model; some big players, like Barclays, have shut down altogether. Mobile money has put tremendous power in the hands of small and medium enterprise owners – the majority of whom, in Kenya, are women – to negotiate not only with banks and other financial institutions, but also with the government itself.

Significantly, in Kenya’s dual system, the mobile money platform has reduced the need for the biannual rural-urban migrations that were becoming not only prohibitively expensive but also unsafe, given the general awareness that people within that travel profile were likely to be carrying significant amounts of cash. During the 2007 post-election violence and the 2020 Covid-19 crisis, when urban areas in Kenya were locked down to outside visitors, mobile money systems were a lifeline for rural communities who could still access their remittances. The mobile phone has sustained lives through some of the most difficult moments in the country’s recent history.

The mobile phone today is ground zero for Kenya’s intense political contests.

The state

A nation is nothing more than a network of communities pushed together by history and kept together by a shared understanding of that history, even as the margins of that shared history are routinely challenged by groups outside power. But the nation-state, as the product of many different ideas coalescing into a cohesive and distinct praxis, can equally be studied as an independent actor in its own right. A state is more than the sum of the individual actors that speak or act on its behalf: it draws a line between political, economic and social choices, distinct from the institutions and people that represent it. The choices of the state as a unified body do not always align with the best interests or practices of the individuals that make up the state. This perhaps explains why, in Kenya, the national interest towards mobile phones seems to constantly pull away from the interests of the citizens. As an object, the mobile phone has become the vehicle for the state to advance some of its worst instincts, including punitive taxation regimes and surveillance leading to arbitrary arrests and detention. The government of Kenya is the largest shareholder in Safaricom, which controls more than 85% of the market share in the Kenyan mobile telecommunications space; as such, the state has a direct financial interest in Safaricom’s profitability. But research has confirmed that the state is not just a silent partner in Safaricom; in 2016, the police confirmed to the UK digital rights charity Privacy International that if they want private customer information from Safaricom, all they have to do is ask.

Moreover, Kenya is a state deeply fragmented along class and ethnic lines, and every election year results in political violence instigated by powerful people trying to disrupt the vote. Mobile phones have also been implicated within this system in relation to the dissemination of hate speech in the 2007 and 2017 elections. The National Cohesion and Integration Commission, formed in 2008 with the task of preventing the dissemination of hate speech, has also used mobile phones as a platform for promoting peaceful dialogue, but they concede that they cannot track or trace everything that gets produced.

In the 2017 election, the advent of new media platforms like Facebook and Twitter showed how far politicians with money were willing to go to influence political opinions via their mobile phones. U.S.-based political consulting companies received tens of thousands of dollars in business from Kenyan politicians to create and push harmful content against their opponents for these platforms. Meanwhile, local politicians in hotly contested regions purchased (or otherwise acquired) phone numbers of their constituents in order to hound them with messages demanding their votes.

Region

The mobile phone is more responsible than just about any other object for Kenya’s unusual contemporary historical arc. Kenya is neither the largest nor wealthiest country in Africa by any metric, yet it is a current leader not only regionally but globally in Internet-related sectors – mobile money, Internet penetration and daily Internet use. Moreover, the vast majority of Kenyans (over 88% according to the last government survey) connect to the Internet through their mobile phones. This has had a knock-on effect on the country’s place in regional politics. The rapid growth in ICT and related services has allowed Kenya to rebase its economy and emerge as a lower-middle income country, even if in material terms much of the country’s population remains poor.

The companies bidding to build technologies include not only those trying to help citizens, but also those facilitating governments in tilting the balance of power away from citizens.

Today, Kenyan ICT professionals are highly sought after both regionally and internationally. The demand for mobile phones has drawn international investment from Samsung, Siemens, Huawei, and other manufacturers. But it has also attracted pernicious forms of investment from international companies that provide the state with the necessary infrastructure to implement surveillance and violate privacy. The global battle for telecommunications dominance has not skipped over Africa, and citizens of countries with large potential markets, like Kenya and South Africa, are stuck in the middle. In their competition to build Africa’s ICT infrastructure, private corporations with decidedly national interests, like Siemens, Google and Huawei, are entering into uncomfortably close relationships with authoritarian regimes. The companies bidding to build technologies include not only those trying to help citizens, but also those facilitating governments in tilting the balance of power away from citizens.

Kenya, a few steps further down the path to a tech-based polity, can provide a great lesson for the rest of Africa. “Leapfrogging” is a myth: without a strong political and civil rights framework, ICT does not simply create “development”– rather, it opens up new avenues for exploitation.

The world

The mobile phone has opened up African societies for both the good and the bad. We are more connected to global discourses and better able to demand visibility on our own terms. We are able to challenge stereo- typical narratives about who Africa is, who African women are. At the same time, we remain vulnerable to new forms of exploitation and consumption by more powerful nations. The most important material in the mobile phone is coltan, the mineral used in the semi-conductors that are the heartbeat of all electronics. Coltan is also a major part of the story of cycles of violence in Eastern DRC, fuelling death, destruction and displacement in East Africa. The DRC is one of the world’s largest producers of coltan – as is neighbouring Rwanda, which has no coltan deposits of within its own geography. It is at the heart of shadowy regional networks of expropriation and consumption.

The socioeconomic dynamics of capitalism encourage choices that prioritise the financial profits of a handful of countries over the lives and welfare of people on the “other side of the world.”

The proliferation of mobile phones all over the world is also part of the growing problem of e-waste, one of the fastest growing types of waste across the world. According to UNEP, in Africa e-waste increases by 20% each year, particularly as wealthier countries sell their e-waste to landfills in Africa in the guise of recycling. Plenty of used electronics cannot be reused or recycled, and some of their materials are extremely toxic. It speaks to the power dynamics between rich and poor countries that African landfills as e-waste destinations sustain a broader pretext of advancements in recycling while posing such harmful consequences to local inhabitants.

Objects are products of human obsessions and interests. Their trajectories through our lives and our societies reflect the choices we make and the processes in which we invest. It was a choice to set up a path for the mobile phone based on endless consumption and rapidly mounting waste; we could have chosen otherwise. But the socioeconomic dynamics of capitalism – a system that we have created – encourage choices that prioritise the financial profits of a handful of countries over the lives and welfare of people on the “other side of the world.” The politics of the mobile phone are contested precisely because they look different depending on who is understood as the user and what level is being examined. All of these contested narratives – the good, the bad and the ugly – are true, and the elevation of certain narratives into universal truth remains a product of our choosing.

“USSD (Unstructured Supplementary Service Data) is a communications protocol for mobile phones that allows for real-time two-way data exchange, such as for mobile web browsing, location-based services, and mobile payments.”