Written by Jolien van der Vaart (Hivos) and Claudia Ocaranza (PODER).

It’s August 6, 2014. Residents in northern Mexico nearby the Sonora and Bacanuchi rivers notice the water is turning orange. But it isn’t until 24 hours later, when dozens of kilometers of river have turned the color of Fanta, that officials at Grupo México report a massive failure of the tailings dam (wastewater reservoir) at their Buenavista del Cobre copper mine.

That delay allowed 40 million liters of copper sulfate and other chemical waste, possibly including cyanide, to spill into both rivers.

The then secretary of Environment and Natural Resources called it the “worst environmental disaster in modern times.” Tens of thousands of people living in seven municipalities nearby were affected. In the days following the disaster, schools closed, water was cut off and residents were in the dark about plans to clean up the spill.

Fast forward to 2020

The toxic spill caused water and soil contamination that has affected some 22,000 people directly and 250,000 indirectly. Affected communities have suffered health damages, loss of livestock and crops, and restricted access to drinking water as a result.

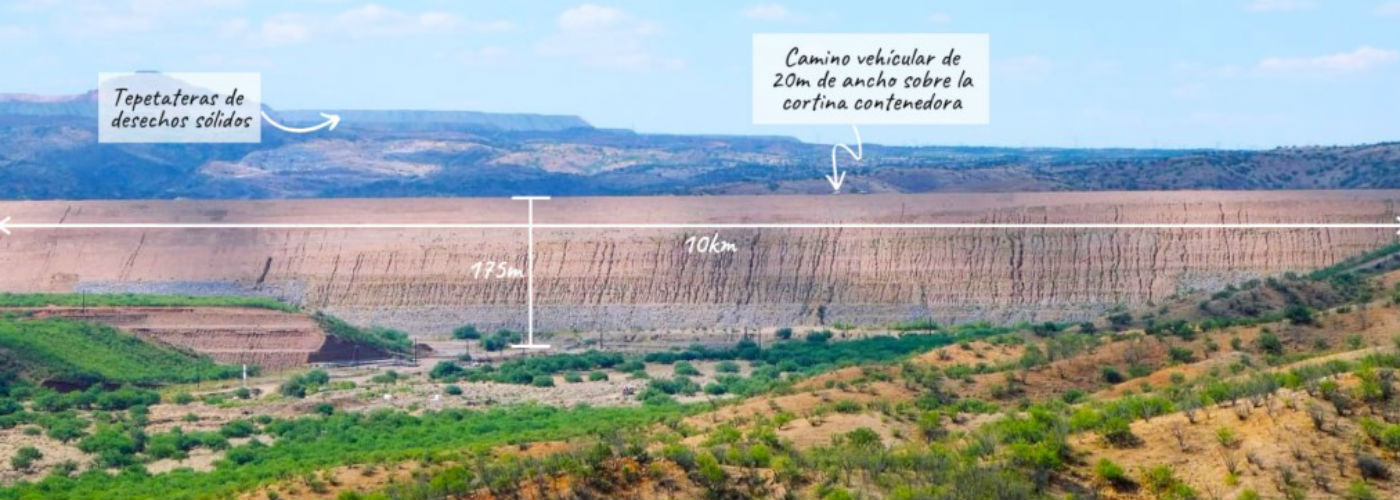

Polluted river, photo: Tom MatthewsBoth the Mexican government and Grupo México were heavily criticized by several UN Special Rapporteurs and a UN Working Group on Human Rights. Yet the CEO of Grupo México, mining tycoon Germán Larrea (good for 15.6 billion euros), now wants to build a new tailings dam that can store over 2 million m3 of toxic waste, equal to 816,000 Olympic-size pools. At the same time, tens of thousands of victims of the 2014 spill are still waiting for compensation.

A powerful transparency platform helps local residents

Faced with the threat of a new mega-dam next door, local communities are demanding action from the Mexican government. And they’re getting support from PODER, Hivos’ Open Up Contracting partner that works to improve corporate accountability across Latin America. Using an online transparency platform, la Nueva Amenaza de Grupo México (Grupo México’s New Threat), PODER is showing how the construction of the new dam will affect the population living nearby.

Together with testimonies, pictures and videos submitted by affected residents, the platform also uses a tool called Tower Builder. It visualizes contracts between companies involved in Grupo México’s new project and the Mexican government. In total, the system tracked payments of 47 billion pesos (more than 2 billion euros) to 42 companies in 1,327 contracts from 2009 to 2019. Tower Builder has also identified 49 beneficial owners of the companies, such as natural owners and majority shareholders, among others.

Why is this important?

PODER maps all relevant information in a way that makes it easy for residents to use to seek redress. The transparency platform has also untangled a murky web of power and stakeholders beyond the mining mogul Larrea, who has yet to apologize or say anything regarding the 2014 disaster.

Collecting and analyzing data on this scale can be painstaking work. Still, in a country plagued by corruption and inequality, making it available to the people directly affected doesn’t only help hold companies and stakeholders accountable. It also gives these same people a say and lets them participate in the decision-making process.

People in the community have since urged the government to publish their plans for the mega-dam, demanded that water quality be guaranteed during and after construction work, and that they be compensated for the 2014 tragedy.

It’s like pulling teeth, but things happen

PODER also provides legal representation to the residents and in this capacity has attended press conferences of President López Obrador and the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources. At first, the questions PODER raised about the continuing lack of compensation were met by empty promises. However, in the last days of 2019, the Environment Minister committed to visit the area and talk to the people who fear the effects of Grupo México’s new project.

A federal judge ordered Mexico’s general prosecutor to reopen a criminal investigation.

The Minister also accused Grupo México of failing to provide compensation to the affected municipalities, and is discussing a fifteen-year plan development plan for the region. This should include new health facilities in the area and access to clean water.

The press conferences and minister’s visit received widespread attention in the Mexican media. On December 29, 2019, a federal judge ordered Mexico’s general prosecutor to reopen a criminal investigation into the 2014 toxic spill. This annulled decisions in 2017 and 2018 to close and archive similar investigations.

While the recent turn of events has lifted people’s spirits, there still remains the question of compensation. Even if it doesn’t bring immediate economic growth or health, compensation would give residents the feeling of justice they’re after.

At the forefront of open contracting

Hivos and our partners have been at the forefront of opening up contracting processes since 2016. We have learned that contracting isn’t and shouldn’t be the sole domain of the government. When more parties are involved, especially those directly affected, better services can be delivered. By sharing and analyzing contracting information, we can save money, create fair competition for business and root out corruption. But these processes are costly, and change doesn’t come overnight, which is why the work of PODER has been so important.

This article is part of a series published in the final year of a unique five-year-long strategic partnership between Article 19, Hivos, IIED and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Under the ministry’s Dialogue and Dissent program, Hivos has aimed to strengthen the influencing power of civil society around the world. You can find more of these inspiring examples in Raising voices around the world.