A new briefing paper has been by developed by Hivos for distribution at COP27 based on extensive research by others and Hivos’ and its partners’ own experiences working with local actors. The paper underlines why money should flow to the local level and showcases promising examples of locally-led climate solutions. It shows ways for international donors and funds, as well as for intermediaries, to increase and secure the effective flow of financial resources to the local level. And it examines some existing mechanisms that increase participation, transparency and accountability and which could better channel much needed resources to these kinds of solutions.

Locally-led climate solutions are widely recognized as more effective because they are designed taking local contexts into account and bring in local expertise and knowledge. They often generate higher social, environmental and economic returns and can benefit the most marginalized groups.

When a community puts its heads together

For example, in Makueni County in southeastern Kenya, affected by both flooding and droughts, residents formed a committee to discuss possible solutions. They built a wall to harvest and hold rainwater and approached the county government for support. Makueni County was able to access funds through the County Climate Change Fund (CCCF) mechanism. This blossomed into a project involving youth, women, and Indigenous groups. The community now has water for irrigation and livestock and to grow food throughout the year. But international funds are needed to scale up to other part of the country.

However, most climate finance doesn’t end up at the local level. Complex rules and requirements in accessing international funding, distant international finance intermediaries, and decision-making powers at only national and international levels prevent local actors from leading climate action or setting priorities for climate policy and funding.

What needs to happen

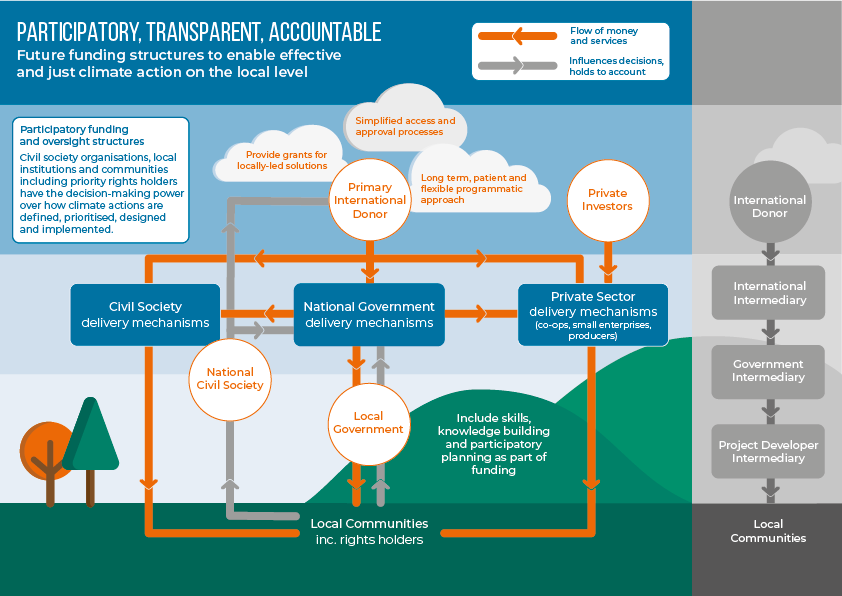

The paper makes three main recommendations. Firstly, create mechanisms for participatory funding and oversight structures to ensure that local actors drive decision making. Secondly, routinely set concrete targets for funds that need to reach climate solutions driven by local actors and provide long term, patient and flexible types of funding. Thirdly, ensure easy access for local actors by simplifying fund application processes.

Promising alternative financing mechanisms

Finally, the paper examines a number of promising financing mechanisms and structures for channeling finance to local communities including priority rights holders. One of these is Podaali, an Indigenous fund in the Brazilian Amazon supported by several donors. It directly provides financial resources to projects of Indigenous communities and organizations that have a social and public relevance. The governance is exclusively composed of Indigenous representatives. All processes are completely transparent and based on legality, impersonality, morality, economy, efficiency and effectiveness.

In conclusion

So there are mechanisms that aim to effectively create capacity, put local communities – including rightsholders – into the driving seat, and channel money to where these communities see fit. What is needed is a paradigm shift that drives international and national stakeholders to change norms of representation and redistribution so that the agency and priorities of groups vulnerable to climate change are at the heart of decision-making. In short, political will to share and redistribute power.