Notes from a community lab at RightsCon 2021

By Conrad Zellmann, Impact Lead for Civic Rights in a Digital Age at Hivos

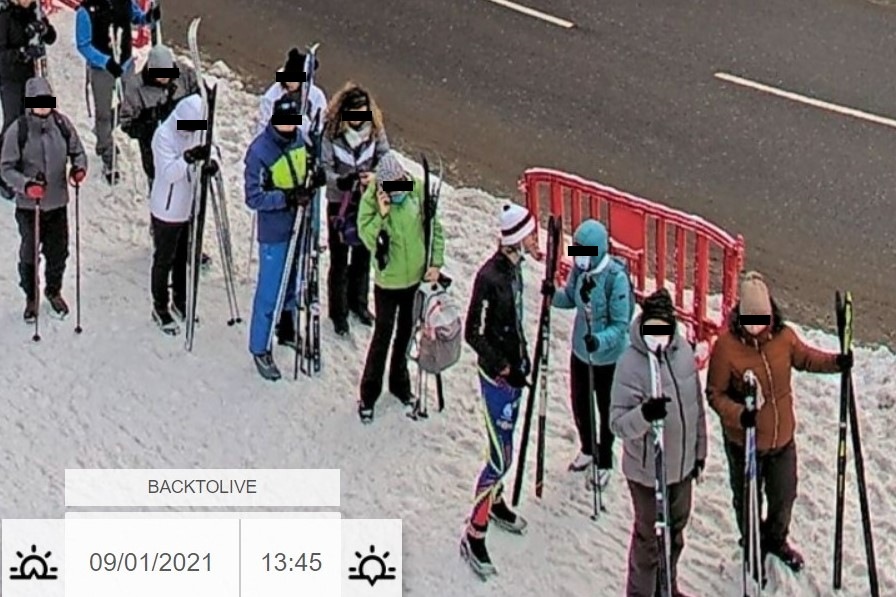

While on winter vacation early this year, I used a webcam to find out about the snow conditions in a small Western European mountain resort where I wanted to go cross-country skiing. Last week, almost six months later, I looked up the footage from the day I was there. Lo and behold, you can see me waiting in line to buy a day pass.

The two faces of technology

Many technologies serve innocuous purposes like mine. CCTV, traffic cams, license plate readers, sensors, 5G, and others can all potentially be employed for desirable ends. Think: safer roads, investigating vehicle theft, or promoting public health. But they can also be abused by law enforcement or private actors to surveil and target people. Without democratic oversight and safeguards, the potential for “mission creep” and harm is significant.

The ground zero of public digitalization

Mine is an example from the countryside. Yet by 2050, more than two thirds of the global population is expected to live in urban areas. Cities around the world are ground zero for the pervasive digitalization of public space. Under labels like “smart” or “safe” cities, governments and technology vendors of all stripes are pushing forward a surveillance-driven approach to digitalizing urban spaces. By the end of 2021, 1 billion surveillance cameras will be installed in cities around the world. Chinese and Indian cities, together with London, lead the pack when it comes to the most surveilled cities, but surveillance is a global phenomenon. Sales of surveillance equipment are expected to treble over the 2016-2025 period, with analysts projecting strong growth in emerging markets.

In particular for people already facing political oppression or discrimination on racial or identity grounds, this presents real threats. Facial recognition and other biometric surveillance technologies are a case in point, playing a role in wrongful detention based on faulty algorithms, enabling political suppression, and chilling the motivation of minority groups to participate in public events.

The push to find alternatives for surveillance technology

If surveillance technology is an urban phenomenon, so is the push to create alternatives to it. A growing body of research and activism points to the harms of surveillance-driven creation of digital cities. From Johannesburg to Amsterdam, independent analysts are questioning the promise of so-called “smart cities”. Use of facial recognition technology has been successfully challenged in various US cities and in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Grassroots initiatives are experimenting with bottom-up, community-driven practices for vernacular digital cities. Activists and researchers are creating digital forensic evidence of urban incidents like the Beirut port explosion and the violent response to 2019 demonstrations in Santiago, Chile.

A few weeks ago at RightsCon 2021, we co-organized a community lab with Edgelands Institute and Experimentalista to explore the harms of and alternatives to urban surveillance. A diverse group of participants from civil society, academia and business discussed a wide range of concerns and ideas: from the need for narrative change (e.g. focusing on “care”, not “surveillance”), to policy options and practical tools for cities; from the role of public procurement as a lever for human rights-based urban tech, to important ongoing campaigns such as Ban Biometric Surveillance and the European Citizen Initiative Reclaim Your Face.

Huge thanks are due to the participants in the lab session, whose thoughtful contributions, examples, and strategies we’re very happy to share in these notes. This document is intentionally brief (two pages), but we hope it’s an interesting and useful addition towards building more public-civic action on the topic. We’re eager for additional conversations on alternatives to surveillance-driven digital cities, and would love to hear from others’ working on this issue.

Postscript

I started off with what may seem like a trivial example. But another situation comes to mind from my childhood in East Germany in the 1980s, when I was about eight or nine. We were on an autumn hike with my parents, their friends and their kids. At some point, someone told a joke about the GDR secret police sitting in manholes to spy on people. Shortly after getting back to town, I saw a manhole cover. I ran over to it and started shouting for the Stasi to come out. The adults, horrified, quickly told tell me to be quiet and to never, ever do that again.

Today’s technology enables much more pervasive surveillance. If we don’t want to live in a world where a silly joke or a serious opinion instils fear and silences expression, we must change the paradigm and practice of urban digitalization.