Earlier this year, we published a call for proposals for theater organizations in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania to submit applications for the production of plays under the themes “The absurdity of Kenya elections” and “African solutions for African problems”.

Theater mirrors the realities in society.

This call was part of the Resource of Open Minds (R.O.O.M.) program’s work aimed at supporting practitioners in the theater industry to bounce back to work after the pernicious effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. As with other works in creative expression, theater mirrors the realities in society. Theater critiques what is wrong, calling society to action and pushing duty bearers to fulfil their duties.

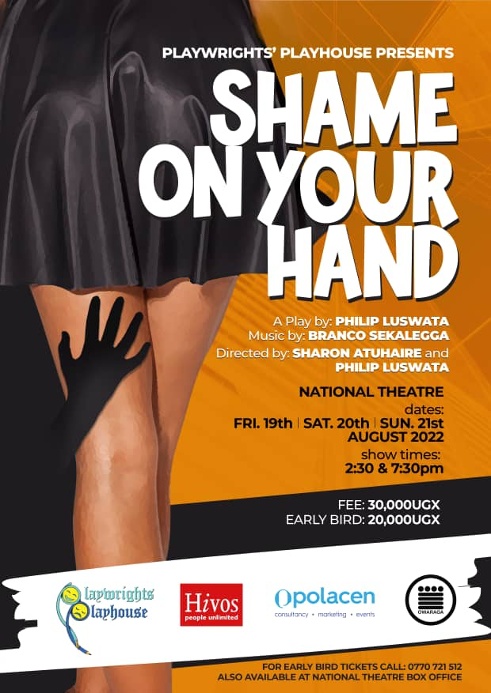

Of the 18 applications received, there were three grantees – Mirror Arts (Kenya), Playwright’s Playhouse (Uganda) and IMO Media (Tanzania). This engagement provided some key lessons for us on the status of theater in the region. Mirror Arts produced a play titled Comrade Masaa depicting the electoral environment in Kenya using the analogy of university elections. Playwrights’ Playhouse produced the play Shame on Your Hand, addressing sexual harassment as inspired by an incident when Ugandan musician Sheebah Karungi was harassed by a fan. IMO Media created a play titled Hatma, themed around how Tanzania had sought ways out of the Covid-19 pandemic. The play was aimed at exposing and criticizing how the lack of adherence to global health guidelines on tackling Covid-19 was costly to Tanzania.

The development of theater in Uganda

To add critical context to R.O.O.M.’s work to restore theater, we asked Ugandan playwright, actor, director and lecturer at Makerere University, Philip Luswata, to share his thoughts on theater in Uganda. Philip has been cast in productions that include Makutano Junction, Queen of Katwe, Rain, Mpeke Town, Honourablez, and Sometimes in April.

“Hivos’ support through R.O.O.M., and the creative independence it affords, is a very welcome shot in the arm during a period when it has been difficult to attract commercial investment in theatre.”

By Philip Luswata, Department of Performing Arts and Film lecturer at Makerere University

Theatre in Uganda since the sixties

Theatre in Uganda has suffered from the policies of those in power that allow them to syphon off what little resources are available for the sector. In the 1960s, Elvania Zirimu, Robert Serumaga, and others made theater productions that questioned the place of intellectuals in the newly-independent Uganda.

Byron Kawaddwa’s allegorical theater questioned the excesses of the brutal Idi Amin regime in the early 1970s. In the late 1970s, the buffoonery showcased by the newly-wealthy smuggler cronies of the government paved way for slapstick ‘Muzukulu wa Kabangala’ comedy. In the 1980s, due to the increasingly repressive political environment, creatives were careful to avoid politics in favor of the safe space offered by social commentary.

The rise of Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army in the mid-80s brought tolerance for the revolutionary political theater of Alex Mukulu and the aspirational theater of returnee refugees such as the Ebonies and Black Pearls Theater. This same era coincided with social concerns including HIV, malaria, poverty eradication, and malnutrition that became key issues addressed in theater productions funded by NGOs. Unfortunately, this relegated commercial theatre to the periphery. People were now able to watch Uganda’s theatre stars for free under community mango tree gatherings instead of having to pay at regular venues.

But by the early 2000s theater had moved from playhouses to bars and lounges and taken the form of sketch and stand-up comedy by the likes of the Amarula Family and Theatre Factory. This is also where the new corporate class that had emerged out of the government’s privatization policies was going for entertainment.

Current status of theater in Uganda

Twenty years later, despite all the Drama and Theater graduates leaving universities every year, the trend of the early 2000s remains. Because comedy is not costly to produce, it is popular in bars that host sketch and stand-up comedy nights all over the country. In the capital, Kampala, where in the mid-90s hundreds of registered theater companies belonged to the Uganda Theatre Groups and Artists Association (UTGA), and there were dozens of playhouses, today you would be lucky to identify anything beyond the National Theatre and Theatre Labonita. Any theaters fortunate enough to still host social gatherings, like Bakayimbira Dramactors’ Pride Theatre, were turned into Pentecostal churches.

Attitude and cultural shift key for change

At present, there is hardly any conscious support for the growth of theater. This in spite of government officials’ frequent pronouncements on how the arts are important for Uganda’s economic growth and provide opportunities for young people. Even the Uganda National Cultural Centre (UNCC), currently better funded than ever, was actually much more effective and pro-artist when it was largely under-funded. So there is a huge need for policymakers to shift their attitude and for government to lead in regenerating the arts in Uganda.

Embracing the digital age for social change

Unfortunately for today’s producers and playwrights, the audience’s attention span has become much shorter. Even more challenging is the fact that the average entertainment consumer today is also a digital content creator used to posting short videos. The days of performances with long-winding narratives and deeper meanings that unfold strategically over time seem to be over.

What audiences want now are quickly-unravelling plots and engaging action snippets that can be uploaded onto digital platforms. And this excitement draws crowds to the concerts of musicians who use these platforms. If theater is to remain relevant in informing social experience, it must find a way to shift along with society onto the digital platforms without losing its essence as an intimate and transformational art form.

Working with Hivos

Hivos’ support through R.O.O.M., and the creative independence it affords, is a very welcome shot in the arm during a period when it has been difficult to attract commercial investment in theater. R.O.O.M.’s partnership with the Playwrights’ Playhouse team used music, dance and drama to explore a theme (sexual and gender-based iolence) that would have otherwise been the reserve of “under the community mango tree” free performances that do not empower the performers much. More of these topics must be liberated from free community theater circles and enter the mainstream commercial theater circuit where the policymakers who can drive change are to be found.

Scaling up quality art for the future

As Philip Luswata points out above, limited investment in the development and dissemination of quality art has dampened the public’s perception of theater as a worthwhile form of entertainment. But the positive public reception of the musical theater play ‘Shame on Your Hand’ by Playwrights’ Playhouse, supported by R.O.O.M., is proof that demand for good theater can be created by providing good theater. So there is a need for the opportunities that R.O.O.M. provides in order to produce quality socially-engaged art that will in turn incubate a new, discerning generation of art lovers and theater goers.