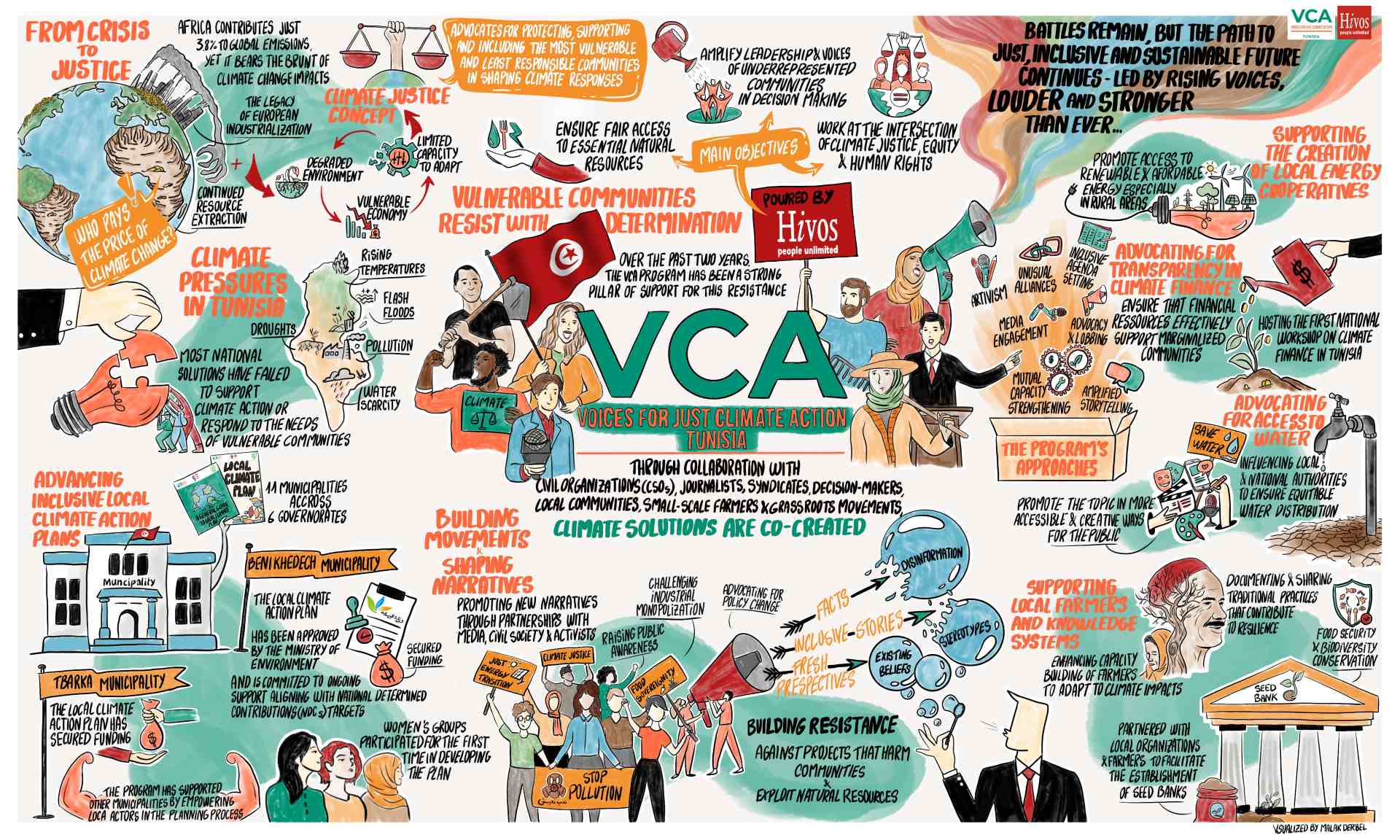

The Voices for Just Climate Action program in Tunisia has just ended. While the program’s work in other countries continues for a few more months, we’re looking back at its results in Tunisia. Program Manager Essia Guezzi experienced it from beginning to end; we’ve asked her to share its achievements and her insights with us.

How did your journey with Hivos’ Voices for Just Climate Action start?

“It actually began before I joined Hivos. I was working with WWF North Africa and was part of the team that designed the program and developed the full proposal. This experience exposed me to participatory design processes and innovative tools like outcome harvesting, risk analysis, and learning-centered MEL frameworks. It was also the first time I used climate justice as a way to expand civic space and create solutions with underrepresented communities.”

Why is climate action needed in Tunisia?

“Tunisia is among the most climate change vulnerable countries in the Mediterranean. Water scarcity is becoming more severe, particularly in the South and the interior. It’s not just an environmental issue; climate change affects food systems, employment, migration, and gender dynamics. Smallholder farmers are facing growing uncertainty due to shifting rainfall patterns, while rising sea levels are threatening coastal communities.

Youth and women are hit the hardest. Yet they’re rarely included in climate policy dialogues. Over time, climate change has deepened their suffering, compounding the challenges they already face: poverty, social exclusion, and marginalization. Add to that the unequal distribution of resources, which reinforces systemic injustice and limits their ability to adapt or thrive.

For climate action to be both effective and just, it must address the issues of the people least responsible for causing it but who are the most impacted. VCA worked to bridge that gap by promoting inclusion, amplifying local voices, and supporting community-led initiatives that demand transparency and accountability in climate governance.”

Can you tell us about the initial plan for VCA in Tunisia?

“The first idea was to create a space where local movements, civil society organizations, artists, and informal groups could come together and collectively advocate for climate justice. Tunisia’s climate agenda has often been decided by a top-down approach. We wanted to change that by shifting power back to the communities most impacted by the climate crisis. We wanted to enable them to voice their concerns, share their lived realities, and together develop responses rooted in justice.

The intention was also to tackle the problem of shrinking civic space. We included those often excluded, such as youth, women, informal groups, and communities that live at the intersection of environmental degradation and social inequality. We moved away from the technocratic or colonial framing of ‘solutions’ and instead centered community knowledge, local resistance, and lived practices as legitimate and powerful pathways for transformation.”

How do you look back on the program now that it has ended?

“The program ran from 2021 to 2024. In just four years, we supported 15 projects, funded 12 civil society and grassroots organizations, co-developed 10 local climate action plans across five regions, and helped produce over a dozen artistic works that brought alternative climate narratives to life.

When I look back, I also see a vibrant community that emerged around climate justice. We worked with artists, farmers, filmmakers, journalists, and youth leaders – people not traditionally involved in climate action. Together, we created podcasts, murals, documentaries, and campaigns. We shifted the discussion from top-down solutions to looking at existing community solutions. Many of these practices – like saving seeds, fighting land grabbing, or defending access to water – are not new. But they are forms of resilience and resistance that deserve recognition and support.

A particularly important outcome that will carry on the legacy of VCA Tunisia is the establishment of the National Advisory Committee for Water. It uses research to advocate for policy changes in legislation, such as the Tunisian legal water code, and builds a strong scientific front to defend the right to water. This scientific body will continue to operate, even now that VCA Tunisia has ended.”

What problems did you face?

“We faced many challenges. Navigating bureaucratic constraints and working within shrinking civic space were major hurdles. Building coalitions across diverse actors with different visions and approaches also needed time and trust. Translating complex and abstract climate concepts into accessible, community-relevant narratives was another key challenge.

But we overcame many of these obstacles through listening, flexibility, and learning. We didn’t follow a rigid blueprint; we adapted and adjusted, often creating new methods with our local partners.”

Lastly, what are you most proud of?

“I’m proud of the community we’ve built – an alliance of youth, farmers, artists, water defenders, and climate activists who now feel more empowered, more connected, and more equipped to act. I’m particularly proud of how we used artivism (where art and activism meet) as a powerful way of engaging people emotionally and politically.

One of the biggest achievements has been the emergence of informal coalitions and networks focused on political and climate issues like energy democracy, food sovereignty, and water justice. These are not just project outputs; they’re living networks that continue to grow and act.

A major success that I’ll never forget is the 2023 advocacy campaign we launched against neo-colonial dynamics in Tunisia’s energy transition. Working with grassroots and informal movements, we demanded transparency and accountability from national institutions. The campaign resulted in over 50 Members of Parliament signing a petition to the Ministry of Industry that challenged opaque energy deals. This significant civic intervention in national energy policy proved that collective action works.

Finally, I’m proud of how we questioned colonial language. The term ‘solutions’ can reflect a colonial mindset, as if communities need to be fixed or saved. In VCA, we learned that many ‘solutions’ are already there: practiced, refined, and protected by communities for generations. Our role was to recognize, elevate, and support them – not replace them.”