The Hivos Women Empowered for Leadership program launched an in-depth, 5-country study on the transformative potential of social media, which can facilitate or hinder women’s leadership.

The development aid organization launched 5 separate reports for Jordan, Lebanon, Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, as well as a consolidated report on the effectiveness of social media as a tool for opening up spaces for women leaders’ participation.

“The conclusions of the five-country study expose social media as a Janus-faced tool that has both enabled and disabled women’s political interests, facilitated and impaired their participation and interests in some instances,” reads the cumulative report.

Researchers across the five WE4L countries identified social media as double-edged platforms. On the one hand, the Internet acts as a free and open platform for women who cannot voice out their concerns and political agendas elsewhere. On the other hand, it opens them up to a “ruthless battleground” where women must endure unending harassment and the reinforcement of damaging patriarchal stereotypes.

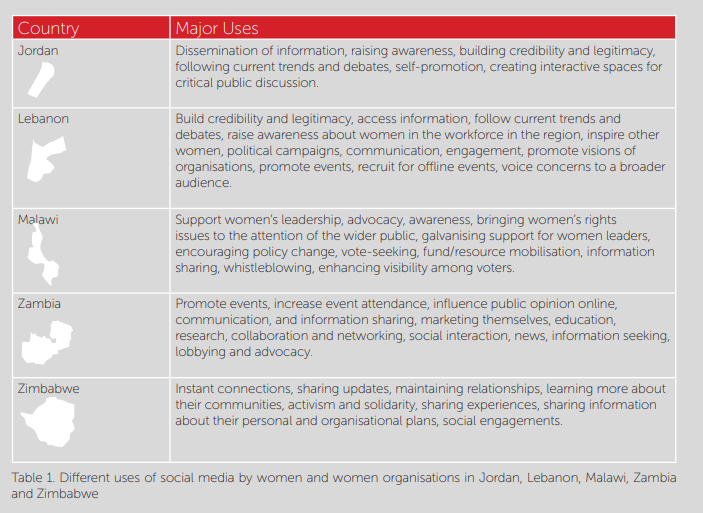

And while similarities span across the five countries, there are also key differences in what social media women leaders and organisations use. In Lebanon and Jordan, Facebook is the go-to platform. In Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, it’s WhatsApp. Additionally, each country identified different major ways in which social media are used –as seen in the table below.

Access to social media is asymmetrical

The social media study’s data revealed economic and class connotations related to social media possession and levels of access. Among the women who have social media accounts, most personally manage them. Some have enough resources to delegate their management to assistants or volunteers.

Additionally, a digital divide is present along urban and rural lines for a variety of reasons. Both the women leaders and their constituents must have access to social media for them to be effective platforms that open up discussion spaces. Rural areas, distant from better-funded capitals and central cities, often lack internet access, consistent electricity, and affordable smartphones –which renders social media irrelevant for constituents living in areas that are less financially well-off.

“Conversations around optimising disruptive technologies as a tool to further women’s leadership interests must account for gender-based income and other household inequalities,” reads the report. “Adopting an intersectional lens on access and use of social media will assist the process of democratising access and control of social media as a resource.”

Downsides of social media

The reports revealed that social media do not replace offline interactions, but rather complement them by providing further opportunities to engage, mobilize, and organize. The report from Lebanon highlighted the possibility of “optical illusions” to emerge with social media presence, which means the presence of a large social media following that is not reflected with on-the-ground mobilization or voting practices.

Similarly, social media automation and algorithms can limit the digital reach of women leaders by creating echo chambers where they’re “preaching to the choir” –or to like-minded people who already agree with them and their political agendas.

Everyone on the internet has their own echo chamber, where ads, posts, videos, and more that suit their interests and thought-processes are more likely to be shown to them.

This includes people with more conservative views and traditional mindsets regarding women in leadership positions, rendering social media a difficult way to alter misconceptions and shift public opinion on women in public positions.

Patriarchal mindsets are mirrored and replicated online, and women’s voices are often muzzled in digital spaces through harassment, verbal abuse, sexualisation, body shaming, and the spread of fake news as was reported by women and groups in Jordan, Lebanon, Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Advice to dealing with such digital abuse often revolves around ignoring it, despite its very real consequences on women’s careers, public perception, and self-esteem. The social media study urges for a more proactive approach in handling online harassment.

Success stories

Social media stand as powerful tools when utilised by women and organisations with the required skill set and dedicated resources to navigate its difficult grey areas. Several case studies from across the five countries reveal as much.

The report from Zimbabwe highlights the #OurBodiesNotWarZones campaign, which exposed denied cases of rape and the arrest of authorities and women who demanded action, as an essential pillar of raising awareness about the weaponisation of women’s bodies during crackdowns.

In Jordan, an article (Article 308) that had allowed rapists to avoid prison by marrying their victims was abolished in 2017 following public pressure and a massive online campaign with 63 organisations.

In Lebanon, independent parliamentary female candidates during the 2018 elections made use of social media to share their political platforms because television advertising costs are too steep and traditional media are owned and operated by heads of sectarian political parties.

“The global findings show that the social media revolution is a nascent regime in formation, whose overriding character is neither all progressive nor all bad,” reads the report.