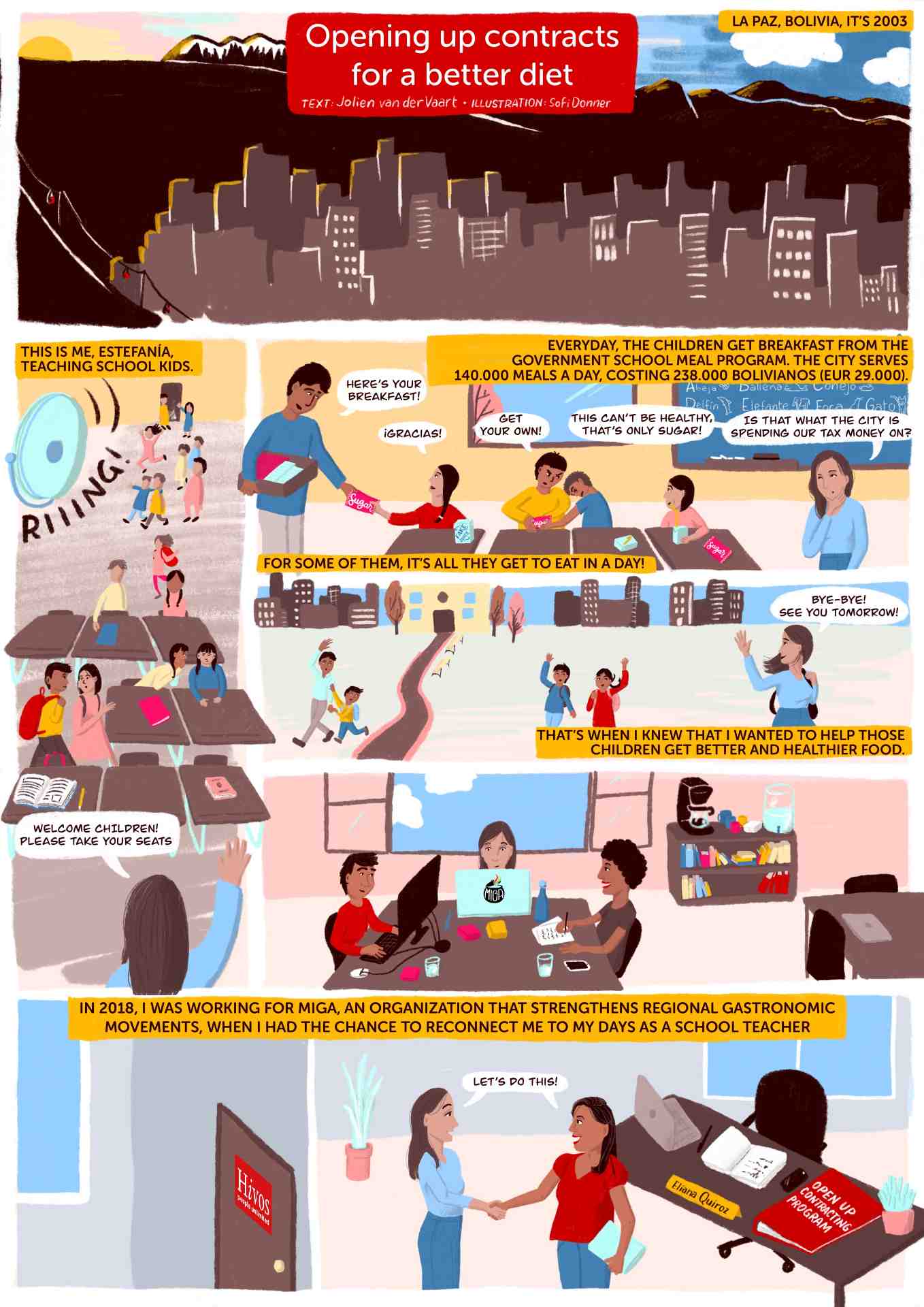

Relying on the school meal program in Bolivia

“How can I help these children get better and healthier food?” Estefanía Rada remembers asking herself this back when she was working as a volunteer teacher at local schools in La Paz, Bolivia. The children in her classes, aged 7 to 10, would eat breakfast at school, thanks to the government’s school meal program.

“I remember how eager those kids were to get this meal, at times nothing more than a cookie and artificially sweetened milk,” Rada says. Not the most nutritious food you’d like your child to have, but even today, it’s the only food that some children get to eat during the day. Their parents are daily wage earners. Some days, there’s enough money to put a good meal on the table. On other days, they have to rely on the government school meal program.

That makes the food the children eat at school very important. It also makes the school meal program an essential government program, not to mention politically sensitive. In 2014, Bolivia passed the Complimentary Food in Schools law (Law 622), requiring schools to feed children from age six to adolescence.

The law also states that local governments should prioritize products from local smallholder producers that promote consumption of healthy food, although it doesn’t make this mandatory. In La Paz, 140,000 school meals are served on a daily basis, costing the city 238.000 Bolivianos (EUR 29.200) per day (ed. data from the first quarter of 2020).

Improving the contract to improve the meal

As in other Latin American countries, public food procurement is a major part of government spending in Bolivia. It has the potential to advance economic, social, environmental and nutritional goals. But if you want to serve healthier food to school children, and source the food from local environmentally-friendly farmers, you need to know which companies purchase what kind of food from whom before you can make contracts.

This is also what Rada wants to know. She now works with the Movimiento de Integración Gastronómico Boliviano (the Bolivian Gastronomic Integration Movement), or MIGA, which supports policies that improve access to sustainable, affordable, and nutritious food.

Once you realize the importance of information, you can empower yourself and help other people.

In 2018, MIGA became a partner organization in Hivos’ Open Up Contracting program. Open contracting is about making data and documents from the entire public contracting process available for everyone. Civil society actors, journalists, and other oversight agencies can then scrutinize processes and drive concrete improvements. This makes public contracting more fair, transparent and inclusive. It leads to better results for governments, businesses, civil society and citizens.

The first step

“Back then, almost no one had heard of open contracting in Bolivia,” says Rada. In order to identify concrete areas of improvement in the chain of school meal contracts, MIGA would have to make the information from the process available and ready to be analyzed. For this, MIGA had to first gather and organize the data.

“The first step we took to create a database was in July 2019, when we dove into the complex world of SICOES. This is the country’s contracting information gateway where procurement information is stored,” Rada explains. While citizens can access this information freely, it isn’t shared in a systematized way that would make it easy to draw conclusions or give feedback.

“We collected all the data from 2014 [ed. after Law 622 came into effect], which made it clear what was being spent on the La Paz school meal program, including how much was contracted and to whom. Then, we had the database we needed to improve the contracts.”

Working with journalists and the municipality

Rada and her team knew that to translate the contracting information into credible feedback for the government, they had to team up with data journalists. So they started training journalists to analyze the database.

Once they got started, her team realized they also had to speak directly with the government to get the whole story. So they hooked up with the La Paz City school feeding unit, one of many other such units that contract companies to supply school meals in the 40 municipalities within greater La Paz. Headed by Gabriela Aro, the La Paz City feeding unit had a good track record that MIGA was interested in exploring.

Aro had then been in charge of the unit for almost 20 years. In that time, she had made many changes to help the children access healthier meals. “She was a rare jewel amongst civil servants and had already improved the children’s diets. But she never understood the importance of the data that she was generating,” says Rada. “We convinced her that her experience needed to be shared with other municipalities, in La Paz and throughout Bolivia, as an example to follow.”

In November 2019, MIGA analyzed Gabriela’s 20 years of public service and created an online repository containing open data on the successful La Paz City school meal programs. To replicate Rada’s best practices, MIGA held an event in early March 2020 for other municipalities in greater La Paz to highlight the importance of systematizing information. Many follow-up workshops on open contracting were also planned.

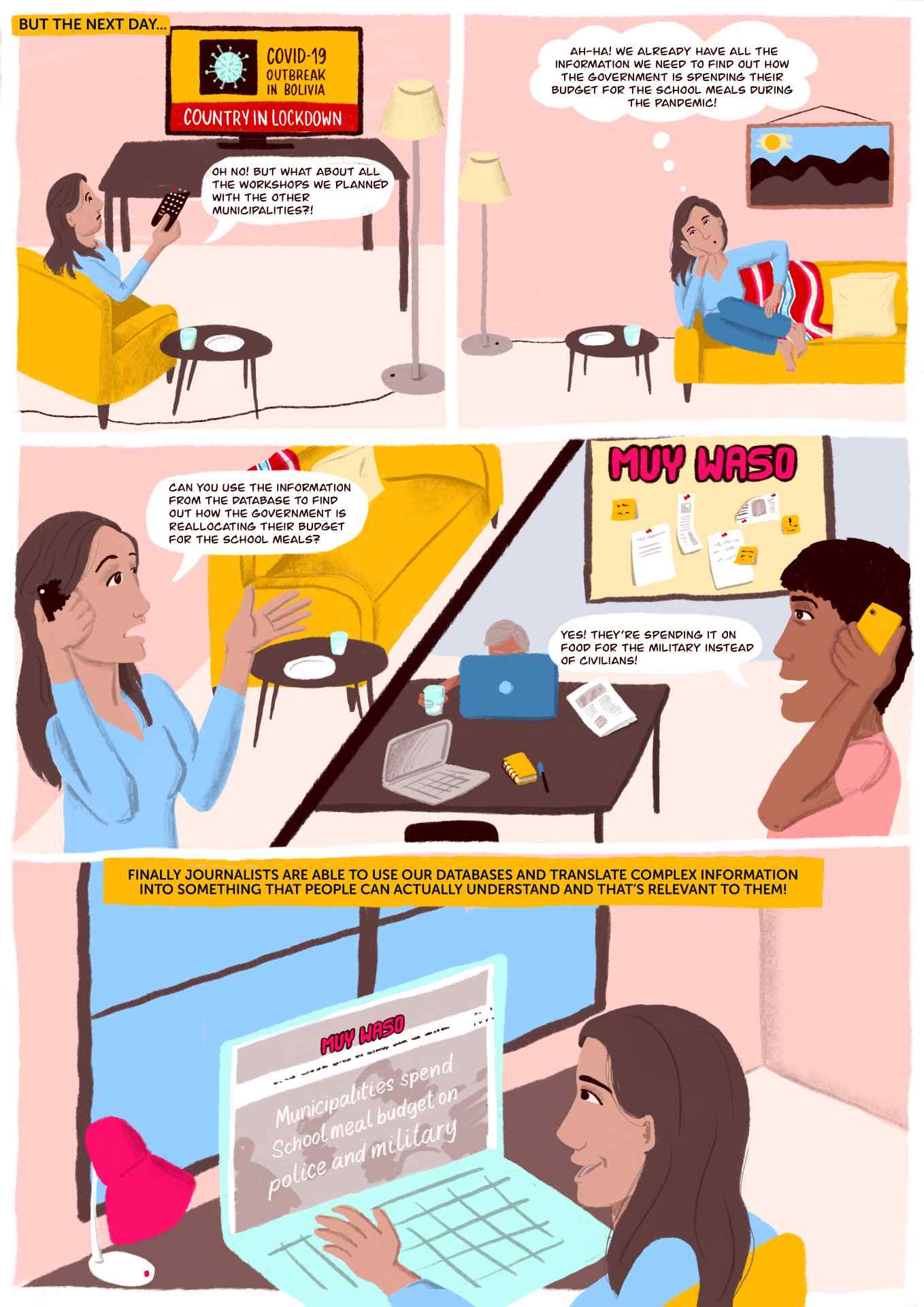

Activism in pandemic times

But on March 10, 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic was confirmed in Bolivia. Two days later, the government declared a national health emergency, closing all public schools and prohibiting large-scale public gatherings, amongst other restrictions. With public schools closed, what was going to happen with the school meals budget? MIGA knew they had to follow the money. They immediately built a database with food contracts from January 2020 onwards to find out how municipalities were now going to spend the unused school meals budget. “Data journalists trained by MIGA were able to uncover how the government decided to reallocate its school meal program budgets.” In an exposé published in August this year, the journalists clearly showed how the government had prioritized feeding the military over feeding civilians.

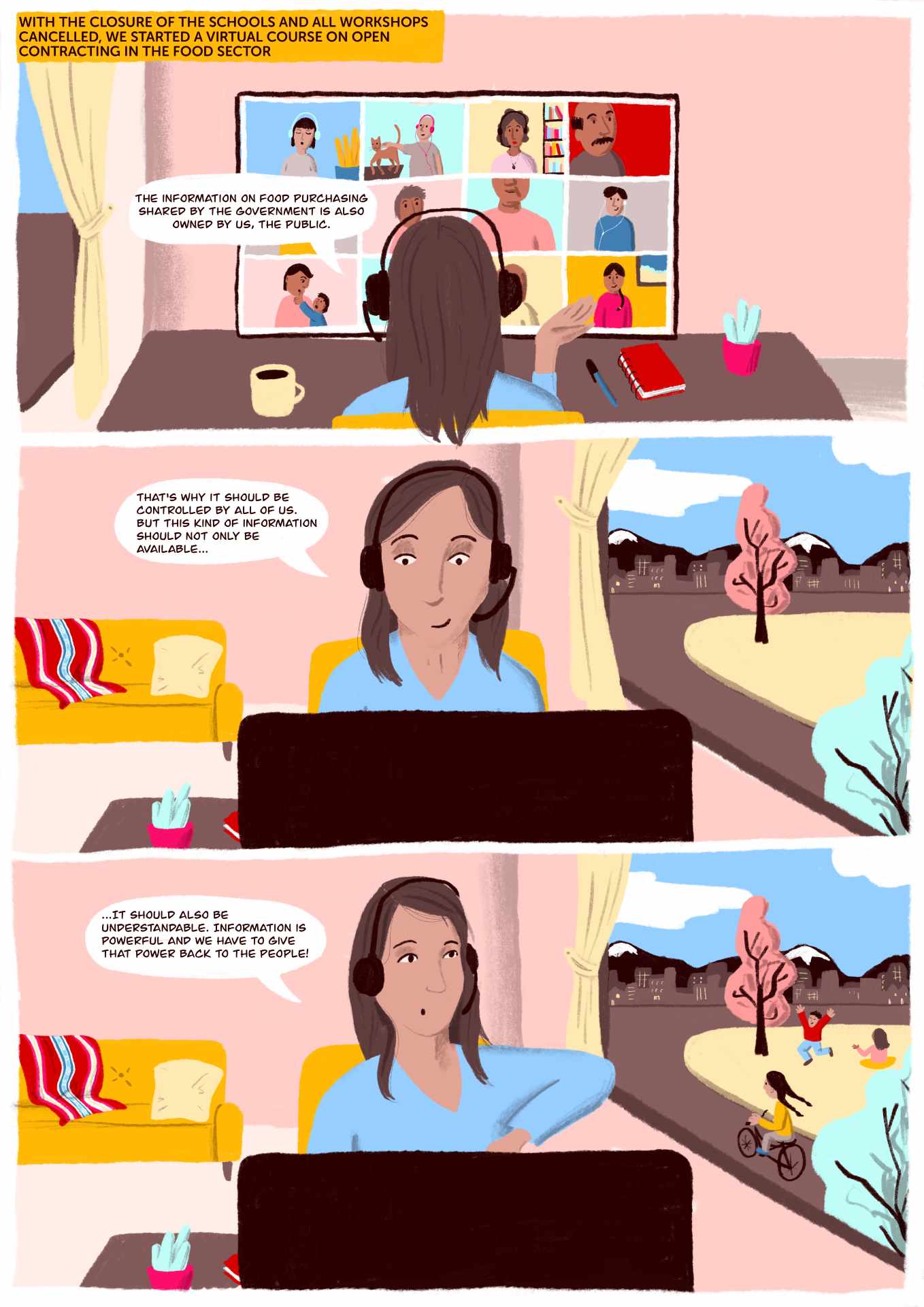

And Rada hasn’t slowed down. With schools closed and the workshops for municipalities cancelled, MIGA is now offering virtual courses on open contracting and food policies. “We always need to keep digging for information because it’s our mission to make the contracting process more transparent,” states Rada.

In fact, Rada has become an open data evangelist and is devoted to spreading the word. “Once you realize the importance of information,” she explains, “you can empower yourself and help other people. The information generated in these public processes is actually owned by all of us and should be controlled by us. Information is powerful, and we have to give that power back to the people. But information is not just good when it’s available. We have to make it understandable.”

Looking to 2021 and beyond

When Rada will be able to pick up where she left off in March will depend on how Covid-19 in the country develops. For now, schools are still closed and the budget for school meals has been reallocated. MIGA hopes that when the situation improves, and schools reopen, it will be able to hold the workshops on open contracting as originally planned. Then it will still remain to be seen whether municipalities put MIGA’s lessons and recommendations into practice. If they do, MIGA is confident this will improve their spending policies and lead to healthier food at schools for the children. As with the proverbial pudding, the proof will be in the eating.