Open contracting: Who benefits?

Guest blog by Francois van Schalkwyk & Miko Canares (authors of the publication Open Contracting and Inclusion)

Peter Garrett, iconic frontman of the politically-attuned 80s band Midnight Oil, while performing ‘Read About It’, would belt out to audiences across the world: “The rich get richer, the poor get the picture”. By the time Garrett bought his first smartphone and the band were selling music online, scholars were warning about the dangers of technology widening existing inequalities. More recently, social movements advocating for greater openness of public institutions are hoping that transparency and accountability will democratise political processes and deliver more equitable benefits for all.

Open contracting is an initiative within the open movement which advocates for better public procurement. This can be achieved by making procurement data more accessible and usable, increasing levels of participation in public procurement, and by ramping up the levels of accountability for government agencies and contractors involved in the award, delivery and monitoring of public contracts.

The argument put forward is that if governments open their contracting processes and data, they can save taxpayers’ money, make better use of national resources, deliver better goods and services, prevent corruption and fraud, create better business environments, and stimulate innovation.

The problem is that while there may be increasing evidence to support these arguments, it is seldom used to test or develop theory. Rather than being abstract or irrelevant, robust theories are needed to understand how, why and under what conditions open contracting succeeds or fails in multiple instances and across a range of contexts.

At the same time, little is known about the outcomes of open contracting, especially whether it leads to greater social equality by including previously marginalized communities such as women, the youth, indigenous groups, and others in public contracting processes. Is open contracting making the rich richer? Or, are the marginalized profiting for open contracting?

It is against this background that we explored the relationship between open contacting and social inclusion for Hivos’ Open Up Contracting program.

We hypothesize that unless open contracting disrupts existing data flows and underlying power structures in society, it would yield limited, superficial, and unsustainable benefits for marginalized communities. One needs to understand how power is accumulated, protected, and disrupted in modern society if one is to design or implement any kind of intervention that seeks long-term social change.

Five cases from low and middle-income countries were selected where inequality and power imbalances are at their most acute to explore the possible benefits of open contracting for marginalized communities in those countries:

- The City Government of Bandung and the Indonesian government’s National Public Procurement Agency partnered to create an open contracting portal (BIRMS). The partnership sought to increase the availability and accessibility of public contracting data and to develop user capacity to make use of the contracting data. Selected local government agencies, the civic tech community, businesses, CSOs, journalists and researchers were invited to participate.

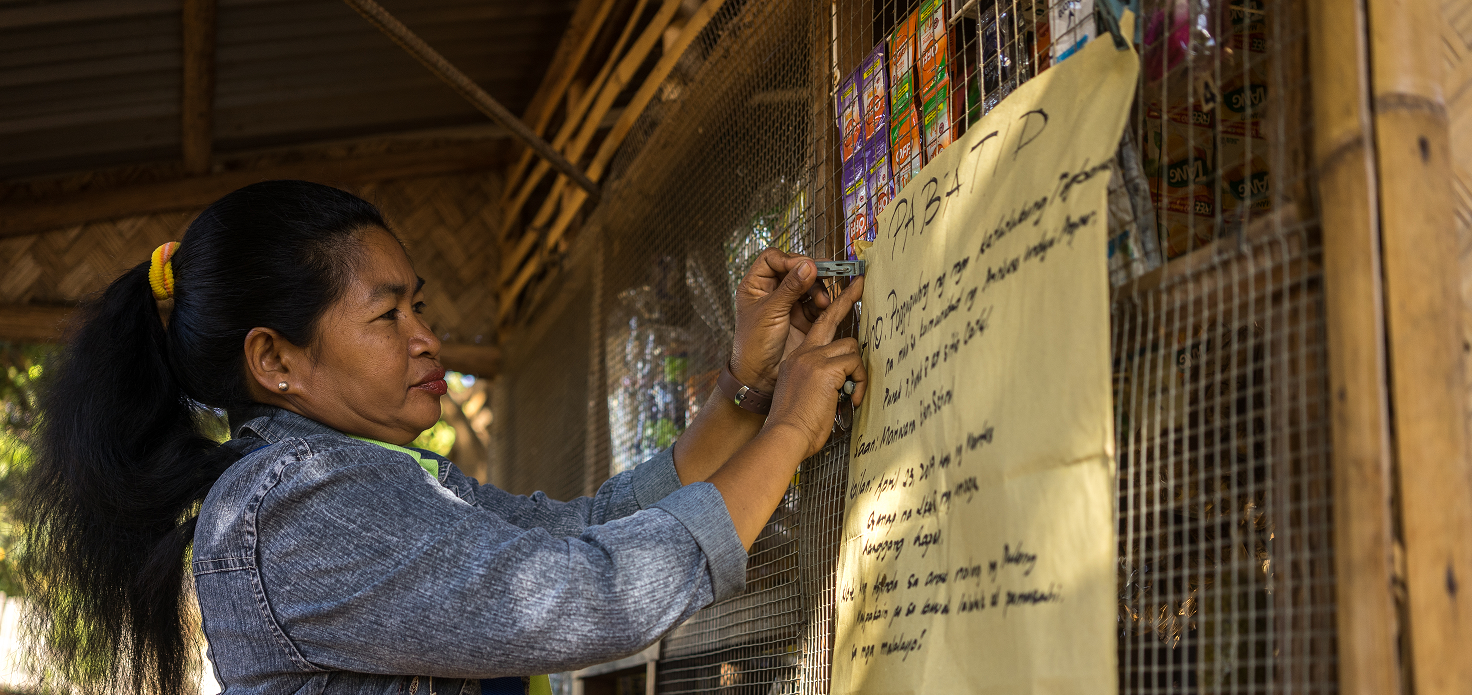

- Bantay Kita, a coalition of CSOs in the Philippines, intermediates between mining companies, government and local communities to improve transparency and accountability in the mining sector. It monitors compliance with legislation to ensure benefits for indigenous communities from mining projects on their ancestral lands. Bantay Kita worked with an indigenous community in Palawan to increase their access, understanding and use of contract data to calculate mining royalties due to them.

- Budeshi is a web platform linking budget and procurement data in Nigeria to various public services using the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS). Budeshi aims to institutionalize the use of OCDS by the Nigerian government and to promote the monitoring of public service delivery.

- In South Africa, preferential procurement legislation was promulgated to ensure more a more inclusive market of public contract beneficiaries. Companies awarded public contracts exceeding a prescribed amount are required to outsource at least 30% of the contract to members of designated previously disadvantaged groups.

- In Kenya, the Access to Government Procurement Opportunities (AGPO) government initiative also aimed for greater inclusivity in public contracting. Legislation prescribes that all government procuring entities spend at least 30% of their budgets on micro- and small enterprises owned by previously excluded groups.

The analysis of the five cases showed that, except for one case, open contracting did not yield significant benefits for marginalized communities. Portals, standards and even legislation did not result in greater social inclusion. This despite the opportunities or ‘opportune niches’ created in each context for new actors to participate in public contracting. The case studies pointed to four considerations that open contracting practitioners should take into account when designing and implementing open contracting projects:

- For open contracting initiatives to be inclusive, they need to be inclusive by design. Problem-centric approaches will reveal exclusionary practices, and will thus point to opportunities for inclusion.

- Inclusive by design is insufficient without an implementation process that is mindful of the inclusive intent. Open contracting initiatives that do not address underlying power structures need to be carefully monitored during implementation to avoid unintended negative outcomes.

- Interventions need to be tailored to targeted marginalized communities. Specific activities need to be designed with the end-goal of enabling excluded communities to participate in and benefit from contracting activities. One-size-fits-all interventions will not work.

- The publication of and access to contracting data is only part of the processes to make open contracting inclusive. There are other systemic hurdles that need to be addressed for public contracting to serve the interests of excluded groups.

We can conclude that for open contracting to deliver social returns, data is not enough. Consideration must also be given to the process of public contracting and the social dynamics in which the process is embedded. In most cases, open contracting data published by governments did not disrupt existing data flows or challenge powerful networks. Published data lacked value in the sense that the data could not be leveraged to challenge those in power.

The successful case of Bantay Kita case illustrated that infomediaries are needed to translate data into problem-relevant information that communities can act upon. Intermediaries are needed to support the actions of communities as they become empowered to challenge networks that protect inequitable distribution of benefits from public procurement. Inclusive problem definition and design, info- and intermediation, and challenging powerful networks are all social processes. In sum, without successfully challenging existing power, marginalized communities will remain excluded from participating in and benefiting from public procurement.

Perhaps Peter Garrett and ‘The Oils’ would have been disappointed by the findings of this research. At the same time, the new insights and pockets of success suggest that it is too soon to give up on the promise of open contracting for marginalized communities.

More detail about each of the open contracting cases and the extent to which they resulted in benefits for marginalized communities is available in the full report of the study.