Can you spot red flags in government contracts?

By Adelle Chua

At a recent investigative journalism conference called Muckraking for the Public Good, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) senior reporter Karol Ilagan talked about the red flags to watch out for when investigating public contracts.The PCIJ, through support from Hivos, has released two sets of investigative reports involving public contracts.

The first series, published in September 2018, looked into the public works contracts awarded to CLTG Builders in the Davao region. CLTG stands for Christopher Lawrence T. Go, who for a time served as special assistant and longtime aide to President Rodrigo R. Duterte. The PCIJ exposed that CLTG had benefited from billions of pesos worth of public works contracts even as it failed to complete projects of that magnitude. In May 2019, largely because of Duterte’s endorsement, Go was elected to the Philippine Senate.

The second series, published in August 2019, was about the Commission on Elections’ contracts with various suppliers during the May 2019 polls, when many malfunctions and glitches resulted in wastage of funds and the disenfranchisement of voters.

Ilagan was quick to clarify that red flags do not, per se, mean there is corruption or wrongdoing. But they do point to leads one can pursue, and can guide reporters on where to take their story.

Across five stages

The most important requisite to detecting red flags is to understand the entire contracting process. Public contracting has several stages – planning, tender (to match below), award, contract and implementation – and documents are made available at each.

Following are examples of red flags that reporters can use in digging deeper into a story.

1. Planning

- Planning is weak or nonexistent. The quality of an agency’s planning can be gleaned from the agency’s Annual Procurement Plan (APP). Good procurement starts with a good APP. These can be found in the Government Procurement and Policy Board (GPPB) website.

- The eligibility criteria are set too narrowly, favoring a preferred company.

- The agency refuses or is unable to make key planning documents available to the public.

2. Tender

- The agency issues bids at short notice, or at an inconvenient time.

- The bid is not well-advertised.

- Items have a vague description.

- There is evidence of bid-rigging. Examples are single bidders, use of indirect awards, multiple contract winners, evidence of collusion. (Collusion is difficult to prove but insiders and documents can provide some clues. For example, the winning bidder provides a substantially lower bid than competitors; the winning bid is too close to the price estimate; the difference between prices is an exact percentage or a whole number; or submission forms have the same handwriting.)

3. Award

- There is a high number of contracts awarded to a few bidders.

- The bidder has no capacity to undertake a project of such magnitude. The NFCC – net financial contracting capacity – is a good way to vet contractors.

- There is a dummy contractor, or a contractor is related to a politician.

- There is evidence of subcontracting with another entity altogether.

4. Contract

- There is a large difference between the contract award and the final amount.

- The final contract amount is higher or lower than industry average. The Department of Trade and Industry and the Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System (PhilGEPS) websites are especially helpful because they show prevailing prices.

5. Implementation

- The project has been delayed or extended beyond the projected timetable.

- Payment has been released despite poor or no delivery.

- Variation orders are issued after the contract award.

- The project bears the names and photos of politicians.

- The contract is modified after it has been awarded, making it even more favorable to a chosen company.

- The agency turns a blind eye to shoddy implementation.

Don’t jump to conclusions!

Amid these red flags, Ilagan warns strongly against jumping to conclusions. She offers the following tips:

- Investigate sources for biases. Coming up with an in-depth investigative report can take anywhere between two and six months, and this is plenty of time to look into your sources to see if they themselves have some hidden agenda.

- Look for hidden variables, privacy or legal issues that could possibly lead you to the wrong conclusion.

- Confer with experts or anybody who is familiar with the project you are looking at.

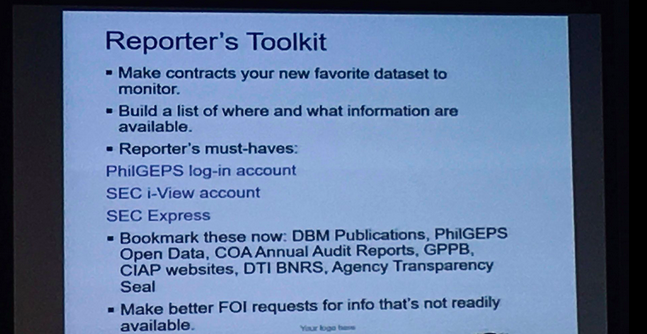

- Build your toolkit. Make contracts your new favorite data set to monitor. While the general environment makes it difficult for ordinary citizens to access data, there are ways we can obtain documents, primarily through PhilGEPS, a creation of Republic Act No. 9184.

Specifically, a good toolkit contains:

- a PhilGEPS login account for checking public procurement records;

- a Securities and Exchange Commission login account for checking corporate records;

- other useful government websites including the audit reports from the Commission on Audit;

- and a well-crafted Freedom of Information request. Know exactly what document you are looking for, and then zero in on your FOI request making sure it will be responded to favorably.

Ilagan’s final piece of advice is to highlight the consequences of the potential irregularity as indicated by the red flags. In writing the story, reporters must focus on the effects of delayed projects or faulty contracting: If a project is delayed, traffic will be heavier, lines will be longer. If a contractor is not capable of delivering a sound school building, the safety of children may be compromised.

The public will better appreciate the importance of transparency in public procurement if they are able to picture the dangers and evils it prevents.