id=”447″ id=”post-1117″ class=”wp-post-content-block ” itemscope itemtype=”http://schema.org/BlogPosting” itemprop=”blogPost”>

Lebanon Support workshop maps barriers and recommendations for female political participation

By Laudy Issa

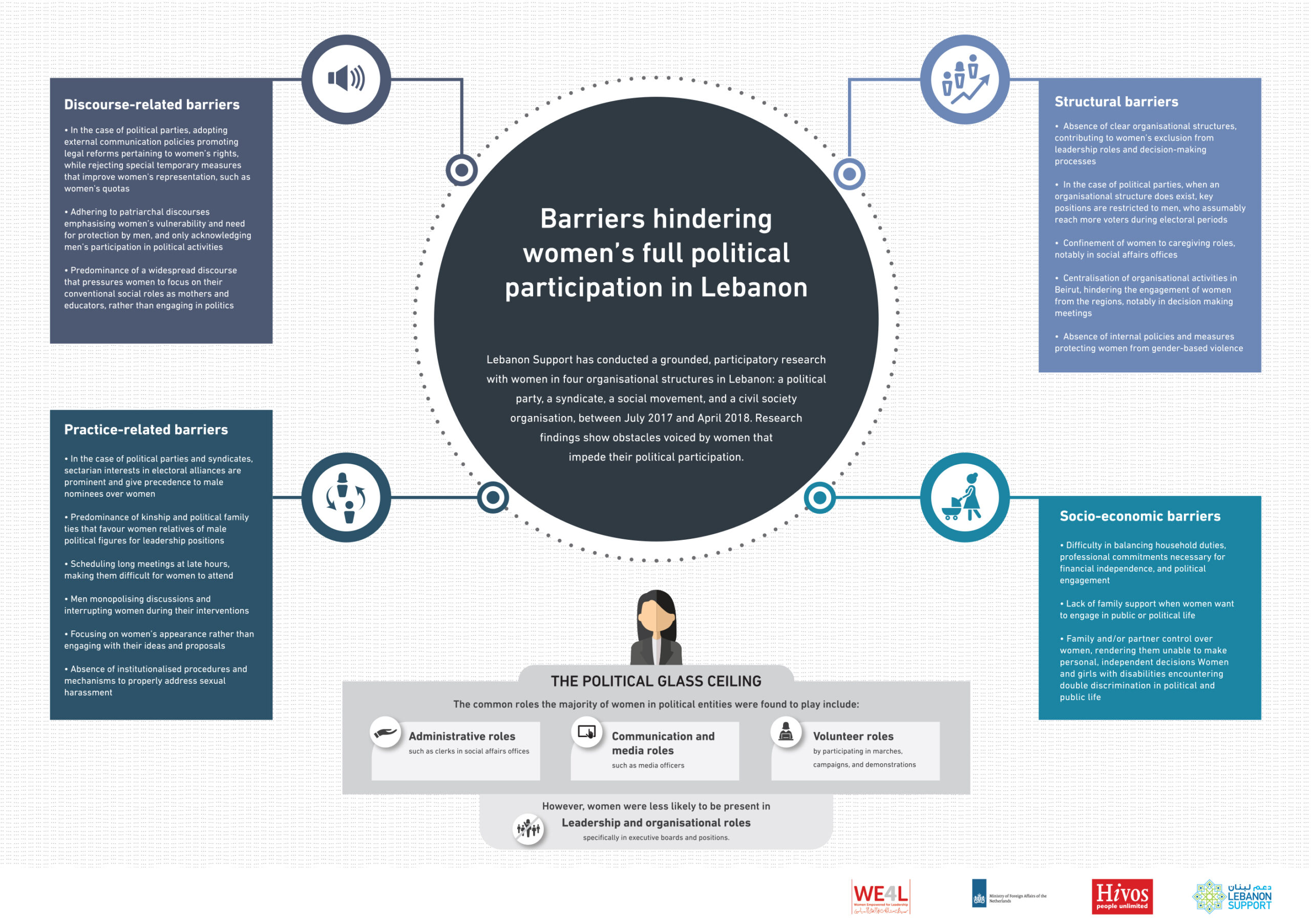

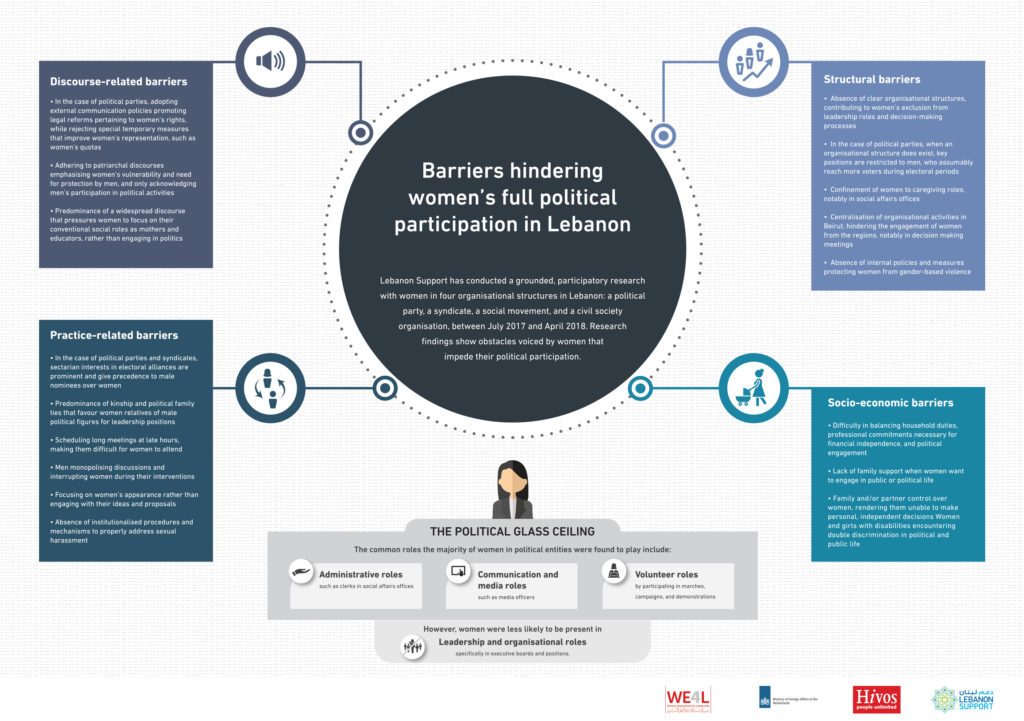

Representatives from different organisational structures in Lebanon set strategic recommendations to increasing and improving the political participation of women, in a closed workshop hosted by We4L partner Lebanon Support following the launch of their recent study.

The closed workshop, held on November 9, also highlighted the findings of the “Women’s Political Participation: Exclusion and Reproduction of Social Roles. Case Studies from Lebanon” report, which goes beyond general questions to take a deeper look at female participation in political life by tackling specific structures in the country.

“We based this study on the idea that the subject is more than just numbers and percentages,” said lawyer and human rights trainer Manar Zaiter, who co-authored the study and led the discussion in the workshop. “The report tried to study the effectiveness of women within four organisational structures, their positions and roles, the documentation and formality of their roles, and the discourse of these structures on feminist causes.”

In addition to discussing the access of women to leadership positions in the “Lebanese Forces” political party, the “You Stink” social movement, the “Teachers Syndicate of Lebanon,” and the “Lebanese Physically Handicapped Union (LPHU),” the workshop investigated the barriers impeding the involvement of females in politics with several of the female research participants from these organisational structures to deliberate means of enhancing women’s political participation in their respective institutions.

Discourse-Related Barriers

By interviewing women from the four political structures between July 2017 and April 2018, the grounded and participatory research revealed the emphasis on female vulnerability and pressure on women to adopt conventional family-centric and caregiver roles within the predominant discourse. Participants at the workshop also discussed how causes related to females are sidelined or considered unimportant with respect to organisations’ more pressing targets, such as sectarian interests and the race to win Parliamentary elections for the Lebanese Forces or the need to ensure protesters head to the streets for the You Stink movement.

To overcome discourse-related barriers, the Lebanese Forces representatives in the workshop suggested increasing awareness among both males and females through workshops and events, to make use of the existing network of male allies, and reforming the discourse itself by highlighting feminism and the barriers facing women in politics as a shared struggle that benefits the organisation itself, not just women.

Structural-Related Barriers

Despite the presence of women in politics, they commonly play administrative, communications, or volunteer roles rather than hold leadership and organisational positions on executive boards. While around 75 percent of its members are female, key positions in the Teachers Syndicate are often restricted to men.

Farah Alcheikh Ali from the LPHU, which also has an executive board mostly comprised of men, suggested the need to reform laws, by including quota systems within political parties for example, as a solution to structural barriers faced by women in political institutions. In her organisation’s case, Alcheikh Ali emphasised gender sensitising laws by including “special items related to women with disabilities,” who often experience double discrimination in public life due to their status as both women and individuals with physical disabilities.

Socioeconomic and Practice-Related Barriers

Participants at the conference suggested the need for collective child care or transportation, to help ease the familial burden off women and deal with socioeconomic barriers facing women. By providing communal childcare or public means of transportation set up by the political organisation itself, women are more likely to be able to attend late meetings and balance household and professional duties with political participation.

The research interviews also revealed several other barriers that hinder women in politics, including the lack of documentation of females undertaking leadership in the Lebanese Forces and the absence of institutionalised mechanisms to both address sexual harassment in You Stink and measure the transgression of women’s rights in the Teachers Syndicates. Another key factor that defines the effectiveness of females in political position is their reason behind joining the political organisation, which, for women in the Lebanese Physically Handicapped Union, is often finding a safe space away from wider societal discrimination rather than fighting for their rights.

Lebanon Support will be releasing a policy brief based on their research findings and the suggestions discussed during the closed workshop.