Frustrations lead to new beginnings

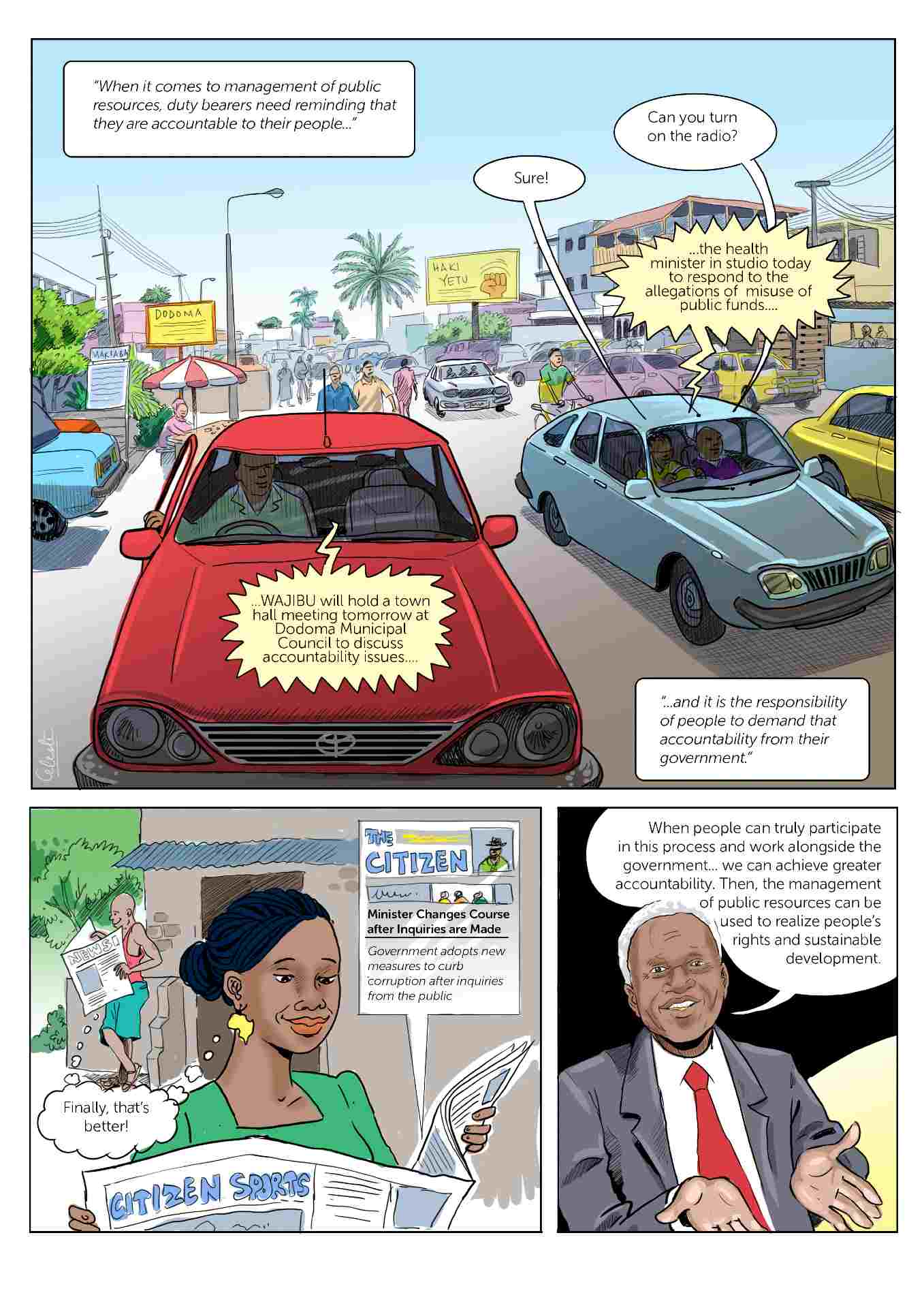

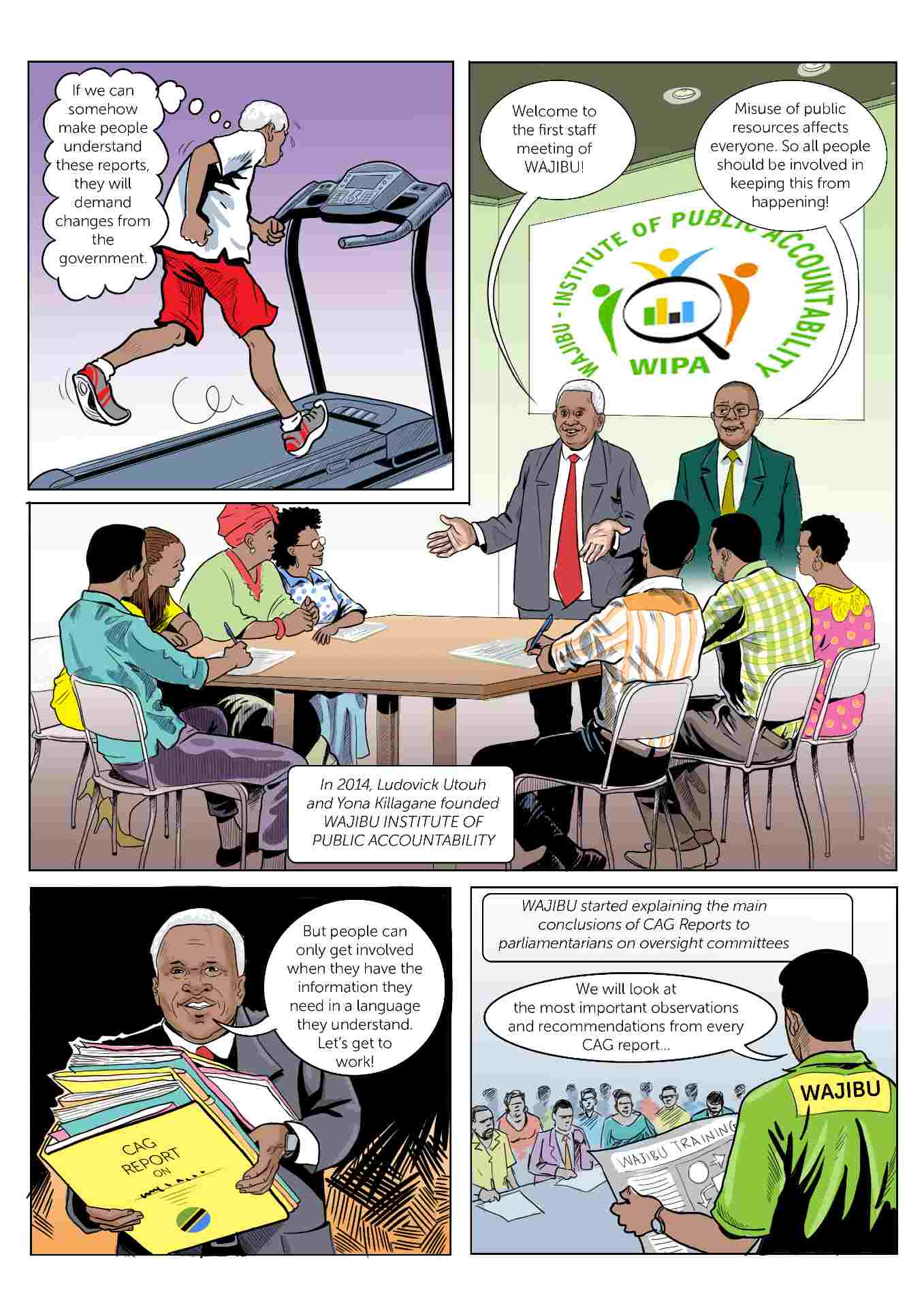

“It was clear to me that there was a need for such an institution in Tanzania,” says Ludovick Utouh, founder and executive director of the think tank WAJIBU - Institute of Public Accountability. Amongst others, WAJIBU informs and mobilizes public opinion about accountability in the collection and use of public resources by duty bearers and elected officials.

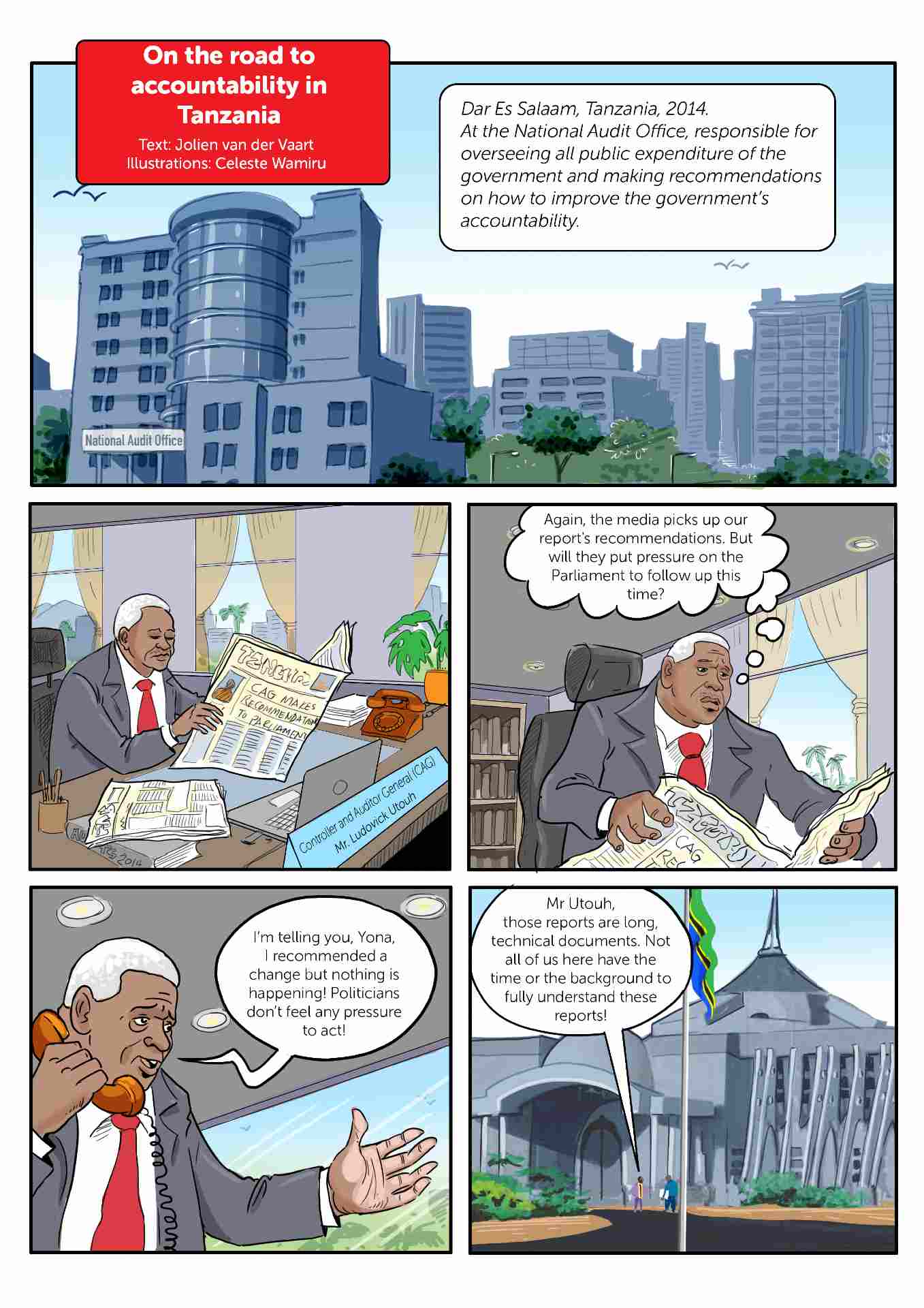

Before Utouh founded WAJIBU, he worked as the Controller Auditor General (CAG) of the government of Tanzania. The office of the CAG is responsible for overseeing all public expenditure of the government and providing annual audit reports. Under Utouh’s watch, Parliament had begun to publicly debate these reports to improve the government's accountability in the use of public resources.

“While I was CAG, I was able to modernize the audit functions in the country. But it was also very frustrating whenever I saw that nothing came from my recommendations,” Utouh sighs. “At times my recommendations would be picked up by the media, but their reports never triggered any real pressure from the public on the duty bearers to act. The public’s understanding of good governance was too limited.”

“I soon realized that unless issues around accountability were people centered, real government accountability would remain a pipe dream. But for people to demand accountability, they needed to be better informed. This pushed me to establish WAJIBU after I retired, which I did together with Yona Killagane, the retired managing director of Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC).”

Utouh and Killagane discussed the gap WAJIBU could fill in government and civil society. While there were already NGOs tracking public expenditures of lower level government, they noticed that no NGO was working on accountability at national level. That’s where WAJIBU stepped in.

Report highlights in the public interest

With a staff of seven, Utouh started to put out Accountability Reports, highlighting the key points of the CAG audit reports - and still does today. “Those reports are big, technical documents of hundreds of pages that are difficult to read,” laughs Utouh. “You can only improve the uptake of recommendations in the reports if people understand them. We provide clear information so others are able to demand accountability,” he adds.

“Once the reports are presented in Parliament, they become public documents. That’s when WAJIBU steps in. We analyze the documents and identify what we consider to be of public interest. We look at the observations and recommendations in each report, why they are important for the development of the country, and at times how the parliament should act.”

Only when the people are at the heart of these processes, can we achieve accountability.

WAJIBU then distributes these reports to all key stakeholders. Within the government, that includes parliamentarians working for public oversight committees. These committees are supposed to push for accountability in the country, but their members don’t always have the time or the expertise to read and fully understand the CAG reports. So besides the CAG Accountability Reports, WAJIBU also offers training for parliamentarians to better equip them to sit on oversight committees.

WAJIBU also provides sector-based brochures discussing CAG report findings on water, health, education, and agriculture. Many civil society organizations use them to mobilize their constituencies.

Journalists also play an important role in getting the public to engage with accountability issues. WAJIBU gives guidance to journalists on how to highlight critical issues in the CAG’s Report. This has already proved effective: “One issue from a previous Accountability Report was picked up by the media,” Utouh recalls. “People read it and immediately started to contact the office of the responsible Minister. As a result, inquiries were made and he had to change his course.”

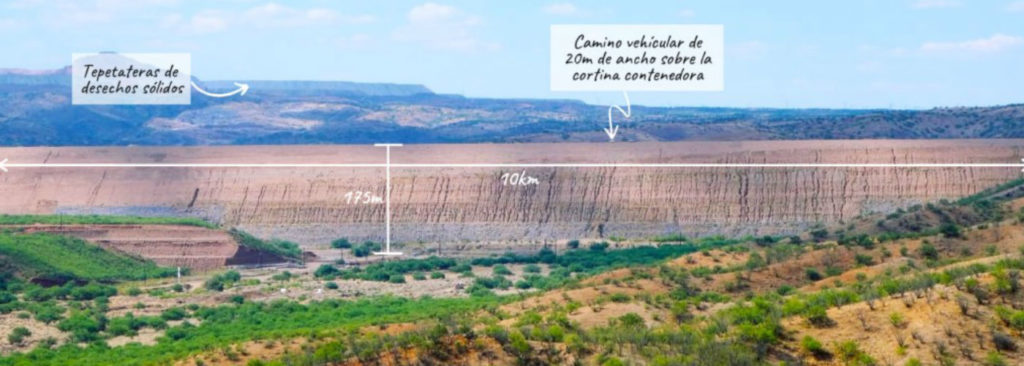

Opening up contracts in Tanzania

In 2018, WAJIBU partnered with Hivos in the Open Up Contracting program. Open contracting is about opening up the data and documents in the public procurement sector. The resulting scrutiny can lead to more effective planning and spending of public funds and encourage civic participation along the way.

“Public procurement is a large chunk of any government’s budget,” explains Utouh. “In Tanzania it accounts for well over 70 percent of the budget. So we immediately saw procurement as an important area to work on accountability.”

Using the Transparent Public Procurement Rating tool, WAJIBU analyzed Tanzania’s national procurement law. The tool, funded by Hivos and implemented by the Institute for Development and Freedom of Information (IDFI), assesses and compares public procurement legislation in various countries. WAJIBU learned that while Tanzania was doing relatively well compared to other countries in the region, there was room for improvement in the implementation phase of procurement projects.

With these findings, WAJIBU was able to interest politicians in improving their spot in the ranking. The tool’s comparative approach effectively stimulated the policymakers to think and act differently.

One problem with Tanzania’s public procurement legislation was that procuring entities were not obliged to include the costs of contracts after the work was completed. “People were taking advantage of this vacuum,” Utouh says. “Now, a new regulation requires this information to be disclosed in an electronic procurement system, and measures are taken against officials who violate the rule. That’s a direct result from our work with Hivos on open contracting,” he smiles.

This change took place after a series of meetings and workshops with government officials in which WAJIBU became a trusted partner. When asked about potential friction during these meetings, Utouh replies that he believes in the spirit of engagement, not confrontation.

“People were hearing about open contracting for the first time, so it was only natural that it took a while for them to understand what it was all about. You can’t come with a new idea and expect everyone to adopt it without explaining how it works. But people are talking about it now and understand it. That’s something I’m proud of.”

Accountability on the horizon

2020 is an election year in Tanzania. Some of the politicians introduced to open contracting by WAJIBU might not be re-elected, but Utouh isn’t worried. “We don’t just work with parliamentarians,” he clarifies. “We’ve also been meeting with career policymakers in their secretariats. Many of them will be back after the election and are convinced of the need to work on this.”

Utouh is proud of the progress WAJIBU has made, as well as its seven staff members. “My staff are thinkers, creators. They can really pinpoint accountability issues in any newspaper story and bring it to the office for us to investigate.” He sees a bright future ahead for WAJIBU and wants it to become a leader on accountability issues.

“The issue of accountability is dear to me. As long as I can think, I will continue to work on it. When it comes to managing public resources, you need to remind governments to act accountably. And the people in turn should understand that it’s their responsibility to demand accountability from their government. Only when the people are at the heart of these processes, can we achieve accountability.”