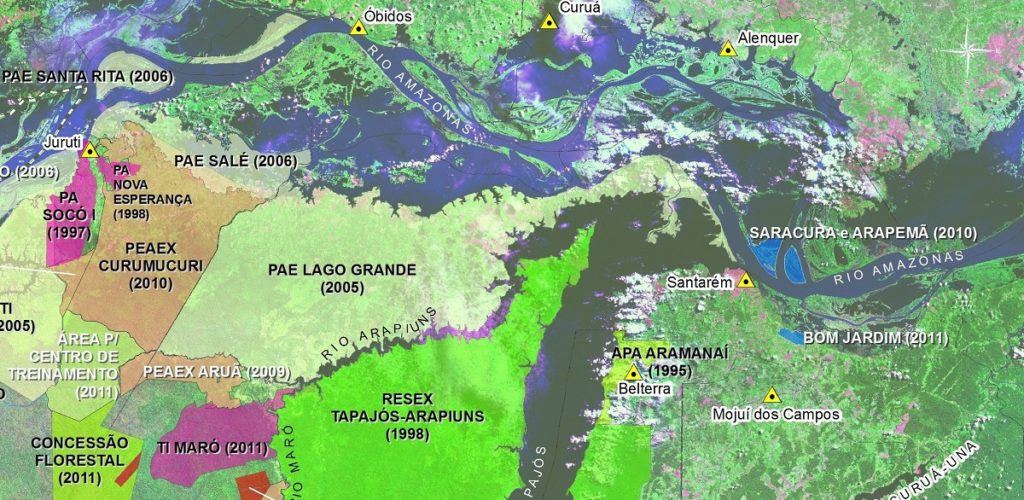

Agro-extractivist settlements in the Brazilian Amazon combine agriculture with the sustainable use of forest resources, creating livelihood for local communities while conserving nature. With climate change and nature-harming activities threatening their way of life, the inhabitants of the Amazonian Agro-extractive Settlement Project (PAE) Lago Grande, are standing strong. A coalition of around 155 communities is advocating for legal rights to their existence and their environment.

FEAGLE – short for The Federation of Residents and Community Associations of the Agro-extractive Settlement Project (PAE) Lago Grande – is spearheading this bureaucratic fight. It represents the 155 communities in the region, fighting for collective titling of the territory and the implementation of public policy.

Maria Selma, vice president of FEAGLE explains the stress the area is under. “Of the territory, 55 percent is mapped for mineral exploitation, this affects 62 communities out of the 155. In addition, land grabbing and illegal logging occur frequently and soybean expansion is knocking on our door.” On top of this, a new climate reality is taking its toll. Fish are dying as rivers disappear, and family farmers are losing seeds, no longer knowing when to plant.

According to Selma, obtaining this legal status for the Amazonian settlements would reduce conflict in the area. “When we get this collective title, we’ll have a better chance of demanding public policies and getting settler rights. This title will stop logging, and land grabs will have repercussions.”

Guardians of good living

In 2019, young people related to FEAGLE started a movement, Guardiões do Bem Viver or “guardians of good living,” in response to mining interests in the area. Since then the movement has grown, and they now address issues such as continuous electricity supply in the communities, access to education and territorial defense.

“Bem viver” is a way of living that maintains ancestral practices and a relationship of belonging and respect, but is also about living in safety. “It has to do with our way of planting and producing,” Thaís, a member of the movement, explains. “We have a relationship with the environment, with the river and its streams, knowledge that has been passed down from generations. We understand that we need to defend this territory so that we, and future generations, can stay here.”

Protecting communities

This includes the fight against climate change and protecting the natural environment where the communities live. In 2023, communities in the upper part of the river started suffering the impacts of logging ports. The water turned red, and bathing in it caused vomiting, diarrhea, and itchy skin. “We became very concerned about these reports. We wondered what we could do to protect the river and our lives, because in many communities people still drink river water, wash clothes in it and carry out other daily ancestral activities,” Thaís explains.

That same year, the Amazon went through a major drought and many of the rivers began to dry up. Feeling powerless, Guardiões de Bem Viver launched the campaign ‘Rights to the Arapiuns river’ to try and find a legal solution for protecting the river from environmental degradation and climate stress. “We are taking this debate to the Santarém City Council, because we also need commitment from council members. We established a committee, a group of people from the communities, that will act as spokespersons for the river. It consists of leaders from communities and villages from the Arapiuns region and different social movements. They will be responsible for monitoring the Arapiuns River,” Thaís explains. The campaign is also consulting lawyers in Santarém to support them.

Mobilizing in preparation for COP30

In May, Guardiòes do Bem Viver organized a pre-COP event for youth, women and community leaders in PAE Lago Grande and neighboring territories to prepare for COP30. “Everyone here is feeling the impacts of climate change, but they don’t know how to talk about what is actually happening,” says Marlon Rebelo, president of the pre-COP event. “We realized that a more accessible narrative was needed, closer to our climate change realities. We wanted to talk about the COPs, but we didn’t really understand what a COP was, and even less how it works.”

Guardiòes joined forces with the University of Brasília and the University of Rio de Janeiro to help them understand how the COP is run in preparation for their event. “We wanted our pre-COP to be a platform for youth from the territory, so we held it in Vila Brasil. That way, others could feel and experience the reality of those who live in the Amazon’s communities,” Marlon adds.

Their aim is to bring people from these communities to COP30. “We are suffering the impacts of climate change, so our future depends on the decisions taken there. But not everyone has the opportunity to be present.” The pre-COP gathering ended with a final document containing the demands of the people in PAE Lago Grande, to be presented at COP30 in Belém by the Brazilian youth representative.

Voices for Just Climate Action

This movement is being supported by Hivos’ Voices for Just Climate Action program. VCA aims for local civil society and underrepresented groups to taken on a central role as creators, facilitators and advocates of innovative climate solutions.