Well-distributed blue and green dots across the Ecuadorian Amazon. That is what we saw when we looked for a map of health facilities coverage in the region. We were brainstorming on how All Eyes on the Amazon (AEA), a program that works to protect the Amazon by defending Indigenous peoples’ rights, could support a Covid-19 response. The map looked like an excellent foundation to work with – the problem is that it did not match reality at all.

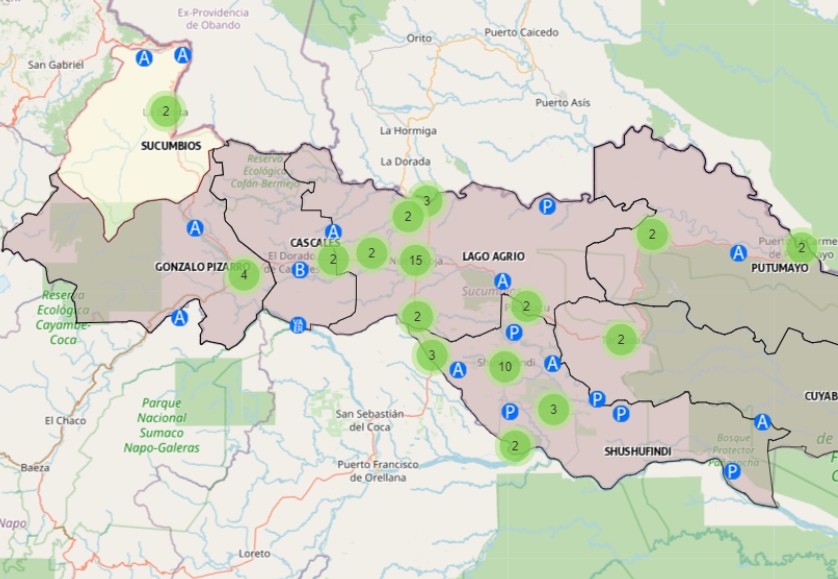

Figure 1. Public health facilities coverage in Sucumbios (one of the Ecuadorian Amazon provinces)

Once the pandemic reached the Amazonian countries where AEA works, we immediately switched our strategy to help with an effective response. Many civil society organizations and multi-stakeholder initiatives focused on addressing urgent needs, such as buying and distributing food kits, water, and personal protective equipment for local communities in the Amazon. We knew these actions would help but that they would not address structural gaps. AEA had a unique opportunity to channel resources from our donor, the Dutch Postcode Lottery, to identify structural gaps in public health systems in the Amazon and find innovative ways to narrow them.

Using geospatial data

And so, we started with maps. We launched efforts in Ecuador, where, using geospatial data on available health centers and services from GeoSalud, a government-run online platform, we mapped 334 facilities in the Amazonian provinces. Specifically, we identified 14 hospitals and 320 first line health services, including itinerant health facilities. As an urban dweller, at first I thought this coverage looked appropriate. Facilities appeared close to each other and, if we drew a direct line between community A and health center B, access seemed feasible.

However, as a team who knows the Amazon first-hand, we knew this first impression does not match the reality on the ground. Maps, as powerful as they are, can miss important details: hills, rivers, and forested paths that, in this case, Indigenous peoples have to navigate through to reach services. Plus, unless the maps’ underlying data includes additional details, often we miss key information, such as availability of resources or health workers at each post. In other words, what looks accessible on a map may in fact require tremendous efforts, and, even after reaching the “nearest” health facility, Indigenous peoples may not find enough supplies and well-trained health personnel.

We heard this first-hand from our partners on the ground. Indigenous representatives and leaders, as well as health promoters, lamented the absence of the state, especially during the pandemic, and highlighted their inability to reach facilities and to find the full services they required. For Indigenous peoples and local communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon, access to health care, and thus appropriate means to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic, was poor, even nonexistent.

A key role for communities

This stark contrast between the map and reality is what inspired what is now The Amazon Indigenous Health Route. In coordination with CONFENIAE (Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon), civil society organizations, and the Ministry of Public Health, and with the technical support of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), we developed a step-by-step model to respond to the spread of Covid-19. Our aim was to improve access to health for Indigenous peoples in Ecuador in a way that is relevant and appropriate for the territorial and cultural realities in the Amazon.

We need to put rights and cultures at the center of public health systems.

In the first months of the Amazon Indigenous Health Route, we identified priority infrastructure and equipment needs in existing networks and micro-networks. We got USD 4.3 million from public and civil society stakeholders to cover those needs and facilitated access to Covid-19 testing. Simultaneously, recognizing the key role communities play in taking care of their own, we worked with Indigenous leaders and community health promoters to strengthen their primary healthcare capacities. They now combine these capacities with traditional knowledge and practices.

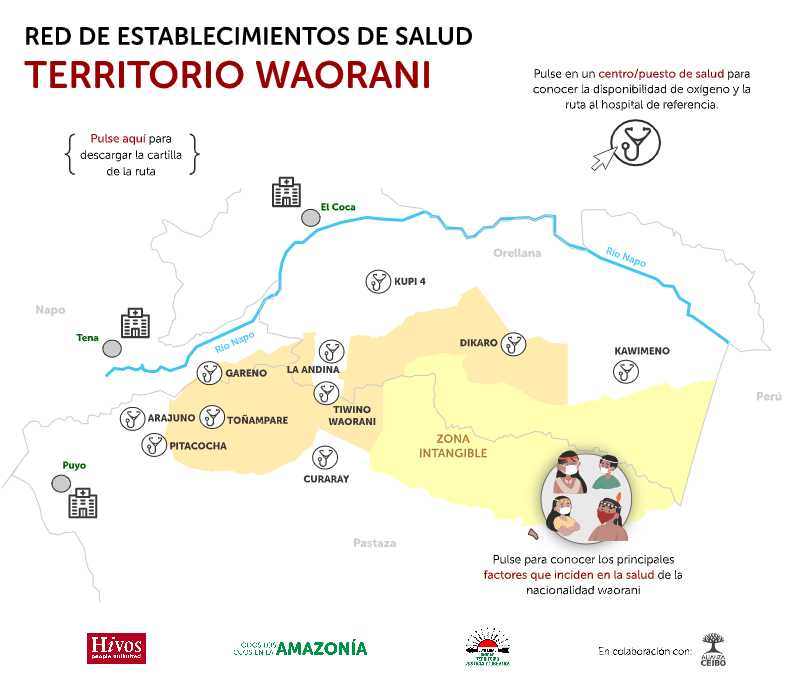

Figure 2. Sample of a health route in Waorani territory

Expanding the program

Since December 2020, with complimentary financial support from The Rockefeller Foundation, Hivos has been working on consolidating the Amazon Indigenous Health Route in Ecuador and adapting and expanding it to the Madre de Dios region (Peru) and the state of Maranhao (Brazil). We are using intercultural knowledge dialogues and working with Indigenous organizations (CONFENIAE in Ecuador, FENAMAD in Madre de Dios – Peru and CTI in Maranhao – Brazil) and the public health systems in the three countries. The dream that began a year ago is now a reality. We expect to contribute to improved access to health and a better response to Covid-19 for 339,000 people from 23 Indigenous peoples and local communities in the Amazon.

Some of the results obtained so far are:

- an integrated health care network in Ecuador

- 17 “Health Routes”, which are step by step tools to facilitate access to health centers and hospitals for 6 nationalities in Ecuador (Waorani, Shuar, A’i Kofán, Siona, Siekopai and Achuar), 7 Indigenous peoples in Peru (Amahuaca, Ese Eja, Harakbut, Kichwa, Matsiguenga, Shipibo-Konibo and Yine); and 8 territories in Brazil (Apinaye, Krahô, Apanjekra-Canela, Memortumre-Canela, Krikati, Gavião Pykobjê, Krepymcatajê and Krenyê)

- operational guidelines for the Vaccination Plan for Indigenous peoples in Ecuador

- capacity-development of 66 Indigenous health promoters and leaders currently participating in the Community Health Promoters (CHP) training program in Ecuador and Brazil

- additional training in prevention, health and community care measures aimed at health professionals, community health promoters and Indigenous leaders

- culturally-adapted, friendly and easy-to-use protocols with prevention and care measures, including vaccination, for Indigenous peoples in the three countries

- expanding the digital surveillance capacity in Indigenous communities and connecting data to the formal health system through a civic application

- production and dissemination of health education materials;

- two thousand Covid-19 PCR tests to support testing campaigns in Indigenous communities of the Amazon

- winning first place in the SDSN Amazonia 2020 Awards (Sustainable Development Solutions Network)

Maps helped me land on a specific site, see the reality of the Amazon, and listen to the people who live there.

I have loved maps since I was a kid. They have shown me how far and wide the world is. I have seen them come to life by navigating their oceans, travelling through their continents, and wandering into their forests. They now inspire my children to travel the world. In this particular case, they also helped me land on a specific site, see the reality of the Amazon, and listen to the people who live there. Covid-19 response strategies will respond to the reality on the ground only when they are co-designed, implemented, and monitored with and by the communities they aim to assist. We need to put rights and cultures at the center of public health systems – and the Amazon Indigenous Health Route aims to do exactly that.